By Brian Tawney

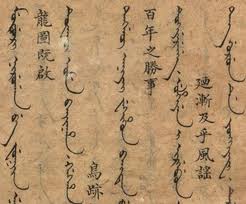

This post is a supplement to Manchu hymn chanted at the occasion of the victory over the Jinchuan Rebels.

The form of this poem is similar to that of the Sibe epic poems Hašigar ucun and Ba na i ucun. This type of poem consists of quatrains with AAAA head-rhyme, meaning that all four lines start with the same consonant, as in this second quatrain from Hašigar Ucun:

han i hese wasiha,

hašigar hūlha be dahabuha;

hafan cooha tucibufi,

halanjame anafu tebuhe.

And this third quatrain from Ba na i ucun:

mergen erdemungge abka ci salgabuha

mukden de amba doro be ilibuha

mutengge saisa leksei sidandufi

muterei teile wehiyeme aisilaha

While the head-rhyme in Ba na i ucun is limited to the first consonant, in the Jinchuan hymn and in Hašigar ucun the head-rhyme extends to the first vowel as well. Head-rhyme is also used in the Qianlong-era couplet poem Mukden i fujurun, as well as Mongolian and Old Turkic verse, including the Mongolian Secret History and Old Turkic Irk Bitig.

In addition to head-rhyme, the Jinchuan hymn also uses the more familiar end-rhyme, with an AABA rhyme scheme. This is found in Ba na i ucun, including the sample quatrain above, and is universal to Jakdan’s seven-syllable quatrains, as in this first verse from Jakdan’s I jy hū be tokoro ucun:

i jy hū, i jy hū,

ujui uju baturu,

abkai banjiha ari,

lii cen wang i deo gucu.

The meter of the Jinchuan hymn is not transparent. According to Amiot, the emperor posed the question: “Can our language not be bound to measured verse, such as is needed to put it into song? It seems to me that this is not so difficult, if one really wants to do it.” If a formal meter was employed in the poem, however, Amiot does not describe it, saying only that it is composed of “stanzas of four verses, of nearly equal measure.”

I think it is possible that this poem generally uses accentual meter, which counts only the stressed syllables in a line, and ignores the unstressed ones. If we apply Jakdan’s basic rules of scansion, and count only the stressed syllables, we frequently (though not always) get the same number of syllables per line. The rules we would apply in that case are:

1) Odd syllables of a word are stressed

2) The last syllable of a line is stressed, whether it is an odd syllable or not

3) Case markers count as part of the words that they follow

Using those rules, we can scan the first two quatrains as follows, with stressed syllables in caps:

JA.ling.GA GIN CUWAN.i HUL.HA,

JA.lan HA.la.ME E.he YA.bu.HA,

JAB.šan.DE MAN.ju COO.ha O.FI,

JAB.dung.GA.la HŪ.dun GI.sa.BU.HA,

AB.ka AI.si.ME GUNG.ge MU.te.BU.HE,

AM.ba E.jen SE.la.HA UR.gun.JE.HE,

AK.da.CU.ka JIYANG.giyūn O.FI,

A.ra.HA BO.do.GON I.le.TU.le.HE,

In each line of the first quatrain, we have six stressed syllables. In each line of the second quatrain we have seven stressed syllables, except the third line, which only has five.

The fact that the line length is not the same from one quatrain to the next is not unusual. In Jakdan’s poetry, couplets vary in length, often starting out short and growing longer. However, the fact that not every line in a quatrain has the same number of stressed syllables implies that the meter was not strict, or else there is something else to be understood about how these lines are read.

The accentual meter is a very interesting study. I knew the head-rhyme as AAAA and the end-rhyme as AABA before, but this is my first time heard the three rules of scansion. Would you mind to talk more about where this conclusion comes from? Is there any paper talk more about stressed syllables in Manchu words and sentences?

sanyūn!

Ha ha, si geli jihe ye~ Saiyūn!

hasuran, Brian’s MA thesis has a good discussion of rhyme in Jakdan’s poetry. It’s a good place to start, as I’m sure his bibliography will have some references. You can get a copy at his website: http://www.manjurist.net/

Thank you so much! This helps a lot. 🙂