Xinjiang’s Xibe Authors: Inspired by “Language of Exile” that has Outlived Manchu

Ironically, thanks perhaps to a centuries-old separation from its origins in northeast Asia, the Xibe language (锡伯语)—closely related to Manchu, the language of the Qing Dynasty rulers—remains a living language in modern-day northwest Xinjiang. Most Xibe are concentrated in Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County, descendants of Manchu soldiers first dispatched in 1764 from Shenyang, Liaoning to garrison the frontier.

Unlike Manchu, a threatened language that reportedly now possesses less than one hundred fluent speakers (10 million Manchus),Xibe still boasted 30,000 native speakers, at least as of year 2000 (Wikipedia).

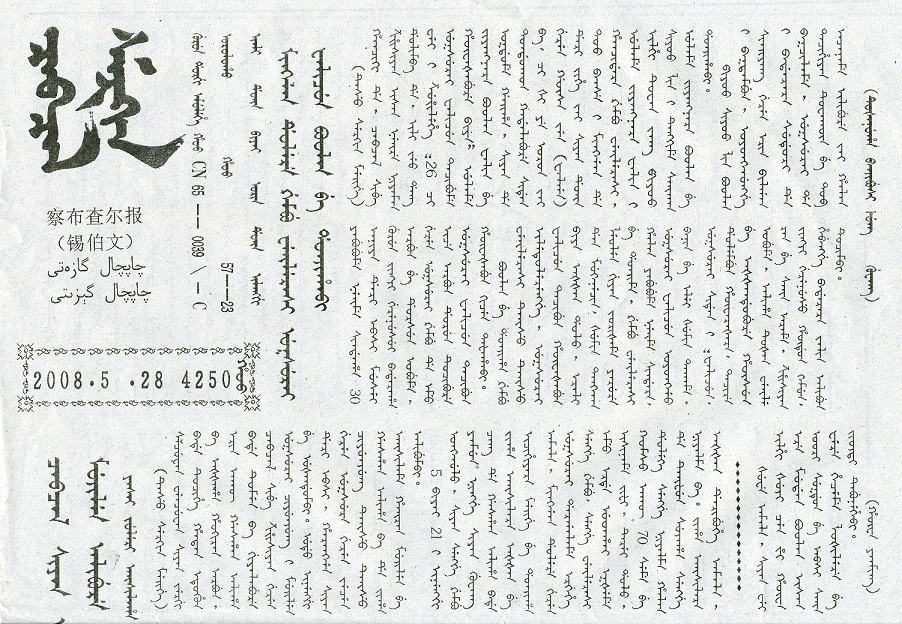

I haven’t been to this area bordering on Kazakhstan, but regardless of how up-to-date those statistics are, one thing is clear: there is an active generation of Xibe authors who can still write in their mother tongue using a modified Manchu script, and perhaps more importantly, can read it and draw on it for inspiration in their works today. This distinguishes them from many non-Han writers whose languages do not possess a written form; they effectively must write in Chinese, and have only two sources for their people’s history—stories passed on by word of mouth, and their history compiled and written most often by the Han.

The China Writers Association recently interviewed four male Xibe authors: Asu (阿苏), He Yuanxiu (贺元秀), Guo Xiaoliang (郭晓亮) and Šetuken (佘吐肯) (锡伯族作家访谈).

The trauma of relocation to Xinjiang from Liaoning, perceived over the centuries as an exile of sorts by the Xibe, is an important theme for poet Šetuken in particular. He is currently writing his own long poem about it (察布查尔畅想曲) , but he has also translated 《西迁之歌》, an epic poem by Guan Xingcai (管兴才) recounting the “migration to the West,” into Chinese.

Like some other well-known non-Han authors such as Uyghur Alat Asem (阿拉提·阿斯木) and Tibetan Pema Tseden (པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན།), Xibe authors Šetuken and Asu advocate trying one’s hand at writing in both Mandarin and one’s mother tongue (China’s Bilingual Writers). Šetuken recognizes that expression in Mandarin is an “inevitable trend,” but he believes that poets who are skilled bilingual writers can ensure less of the ethnic flavor is lost in translation.

“I used to write in Mandarin,” recalls Asu, “but then I began to experiment writing poetry using my mother tongue. Creative writing in your mother tongue means thinking and writing according to its natural rhythms and rules. Just one word in one’s mother language can express so many things, and entirely convey what you’ve imagined.

“But my ability to write in it is not as good as in Mandarin,” he admits. “We’re not like the older generation of Xibe authors. Their grasp of Xibe was no problem at all, and they could express themselves skillfully.”

Post by Bruce Humes, reproduced with permission from his blog Altaic Storytelling