David Porter

Ph.D. Candidate, Harvard University

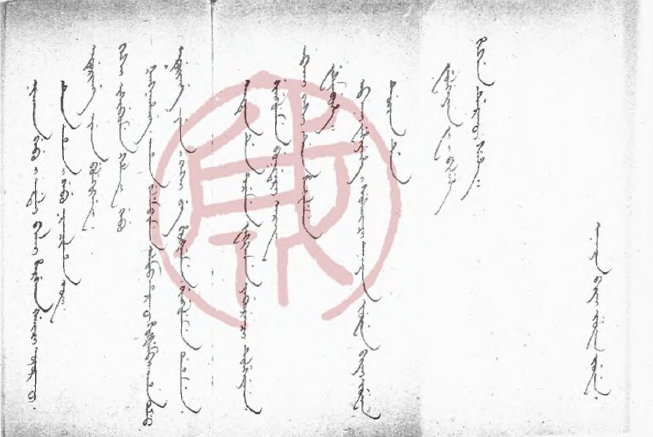

This post is based on a Manchu language lufu zouzhe (錄副奏摺) that I found in the First Historical Archives in Beijing on a research trip this summer. Readers may also be interested in taking a look at my post (also at MSG) dealing with the practicalities of using the FHA and its Manchu language collections.

On the 12th day of the 10th month of the 50th year of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign (that’s November 13, 1785 in the Western calendar), the acting Provincial Judge (按察使) of Guizhou Province sent a memorial to the throne.[1] The first thing that grabbed me about this memorial was the name of its author – Nikan Fusihun – which, in fact, also turned out to be its topic. As those familiar with Manchu will immediately recognize, Nikan Fusihun literally means something like “beneath a Chinese” or “less than a Chinese”; for a translation better capturing the flavor of the insult, we might say “stinking Han” or “Chinese scum.” As you will no doubt suspect, this is not the name that this official’s parents had given him. His original name[2] was Xi-chong-fu (喜崇福), he was a member of the Gioro clan, and his name first came to the emperor’s attention as a result of his memorial thanking the emperor for his appointment to his new post. His memorial of Qianlong 50 is as follows:

“The person I sent to carry my memorial returned with an imperial edict, which said: ‘Slave[3], your name resembles a Chinese name. I am specially bestowing favor on you and changing it, granting you the name Nikan Fusihun.’ Receiving the edict, I knelt and repeatedly kowtowed in acceptance, prostrating myself and thinking, “your slave is a Manchu, of the Gioro clan, so by rights I should take a Manchu name; it would be inappropriate to take a name falsely written as if it were a Chinese name.’ Now, because your slave’s name took a Chinese form, your Holy Majesty has scrutinized it, and bestowing favor, changed it and given me a new name. Your slave thanks you [although] I have not become pleased with it and accustomed to it. Your slave merely, aside from thanking your Holy Majesty for your favor, respectfully obeying you and exerting my full energies in all matters, respectfully wrote this memorial, and memorialized kowtowing to imperial favor.”

This obsequious attempt to suggest that the author didn’t really want to keep such an insulting name, though never saying that the emperor had done anything at all wrong, did not sway Qianlong. Rather, the rescript on the memorial was a single word: “derakū” – “shameless.” Xi-chong-fu seems to have been stuck with the name for the next ten years, when his name may have been changed to Nikan Baturu, meaning “Chinese hero,” which though much less insulting than Nikan Fusihun likely still carried a mocking tone when applied to someone like Xi-chong-fu who was in fact a Manchu.[4]

This memorial, and the episode it describes, do not paint a very flattering portrait of the Qianlong emperor. In a move reminiscent of the well-known petty tyranny of Peter the Great, Qianlong cruelly mocked a minor official who had done nothing wrong other than have a name that Qianlong didn’t like, forcing him to spend ten years being addressed by an insult in any official business he conducted. In addition, it suggests something about Qianlong’s attitude toward ethnic categories: Manchus and Han were separate groups that needed to be kept that way. Moreover, the form of the insult itself – something little more sophisticated than the practice in American schoolyards of my childhood in which anything undesirable was referred to as “gay” – suggests that Qianlong considered Chinese to be an inferior category of person, and that Manchus could be insulted via comparison to them.

[1] It’s numbered 03-0191-0357-009 in the FHA cataloguing system, in case you’re in Beijing and interested in taking a look yourself.

[2] Found through a Shilu entry from Qianlong 49.11 that briefly describes the name change. Even looking at the Shilu, though, knowledge of Manchu is necessary to know what is going on, as someone who did not know Manchu would be unlikely to recognize how insulting 尼堪富什渾really is.

[3] I should note that I am well aware that the use of the term “aha,” meaning “slave,” was quite routine for officials of banner status when writing memorials to the throne. Given the content of the memorial, however, a literal translation seems more appropriate here.

[4] I didn’t find any document ordering the second name change, but the first appearance of Nikan Baturu in the archives is about a year after the last appearance of Nikan Fusihun, and both appear holding the same office: Circuit Commissioner of Guidong.

Note (8/6/2020): Looking back on this document, I realize that there is a mistranslation of one sentence. The sentence reading: “Your slave thanks you [although] I have not become pleased with it and accustomed to it” above should in fact be translated: “Your slave trembles in fear and offers exceeding thanks.” Thus, the claim that the author expressed explicit displeasure with the name he was given was made in error. The basic analysis – that Qianlong bullied an official over his name and forced him to adopt an insulting name – remains accurate.

-David Porter

Thanks for your post. Naming practices among Manchus and the attempts by the court to control them I find quite an interesting topic.

It reminds me of this bit I read the other day in the An i gisun de amtan be sara bithe :

nomun de juwe hergen i gebui emteli ningge be daldarakū sehebi. muse gebu arara de amai gebui ujui hergen be baitalaci ojorakūngge. tere emu hergen be daldara jalin waka. nenehe aniya g’aozung han i hesei ama jui gebui ujui hergen be jursulebume araci. ahūn deo i adali ombi seme. tereci ama jui i uju holbome hergen baitalara be fafulahabi.

Apart from the few pages devoted to this topic in the Manchu Way, do you know of a more comprehenseive study of these questions ?

“which though much less insulting than Nikan Fusihun likely still carried a mocking tone when applied to someone like Xi-chong-fu who was in fact a Manchu”

This is incorrect. Many Manchus had the personal name “Nikan” and it was considered a normal name. For example, Nikan Wailan, the Jurchen chieftain who was Nurhaci’s rival. It wasn’t considered derogatory to for a Manchu to name their child Nikan and in fact Mark Elliot says on page 242 of “The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China”, that “Manchus frequently named their children-at least, males……..-for their appearance, their personal characteristics……for animals, plants, and objects. THus was found names like Nikan (Chinese)…..

Arabs in Saudi Arabia sometimes name their sons “Turki” (after the Turks) even though the Saudis fought against the Ottoman Turks in several wars.

It isn’t considered insulting to name your children after another ethnicity in many cultures. Claiming Nikan was a derogatory personal name for a Manchu is plain conjecture.

Qianlong is also the man who ordered the violent annihilation of the Mongolic Oirat Dzungars in Dzungaria and the violent annihilation of the Tibetic Jinchuan people. And then he sent Han colonists to take their place so that Dzungaria became filled with Han farmers. If he scheduled a certain people for annihilation he flooded their land with Han people after the genocide. Its not like he had a high regard for the lives of any other people.

One of the grandsons of Nurhaci was named Nikan. He was involved with his fellow Aisin Gioro Princes Mandahai and Bolo in supporting Dorgon. The Aisin Gioro named their own children Nikan.

The Jurchen chief Nikan Wailan was a prominent leader during his rivalry with Nurhaci. There is no way that the name Nikan was considered “mocking” to Manchus when their own Imperial Princes and tribal chiefs carried that name.

The name Nikan alone wasn’t offensive, though I think its use was much more common in the pre-Qing period (all five entries for Nikan, or a name containing it, in the MQNAF database are for people born before the conquest), and it’s hard to read Qianlong giving it as a name to someone he had criticized specifically for having a name that was too Chinese as anything other than mocking. I grant that the claim is less incontrovertible for Nikan Baturu than for Nikan Fusihun (which is explicitly insulting – no need to speculate there), but considering the whole context, I’d guess than Nikan Baturu was not meant to be a desirable name. Consider also that the kind of martial virtue associated with the word “baturu” was ethnically coded in the Qing; Manchus or Mongols might be baturu, but to associate “baturu” with “Nikan” was probably understood as a bit of a joke, especially to a Manchu chauvinist like Qianlong.