The Injustice of the Silk Thread[1]

Translation by David Porter,

Ph.D. Candidate, Harvard University

and Devin Fitzgerald

Ph.D. Candidate, Harvard University

In an inner province of China, a man surnamed Chou and his wife had two sons. After their older son was married, they decided on a betrothal for the younger son with the daughter of a man named Zhou. Soon after, the parents of the girl passed away, and because the girl had no close relatives nearby to take care of her, the Chou family took her in as an adopted daughter-in-law.[2]

At the time, the girl was thirteen sui.[3] Every day, when they made her spin thread, they would calculate how much she had spun. One day, a bundle of thread that she had spun disappeared from the place where she had left it and she could not find it. Because of this, Mrs. Chou, who had a very cruel disposition, railed at her excessively, saying that either she was lazy and hadn’t actually done any spinning, or else that she had stolen the thread and sold it for her own profit. She then grabbed a wooden stick and, not even attempting to avoid the girl’s head and face, beat her over and over, telling her to spit out the truth. If she didn’t say anything, she said she would knock the life out of her.

The girl truly couldn’t bear up to the woman’s callous and arbitrary beating and so, hoping to be spared further beating, she said that she had sold the thread to an old neighbor woman. As soon as she said this, Mrs. Chou told her to go and get it back. At this, the girl thought to herself, “Since I never gave her anything, how could I possibly get it back? But, since I already told Mrs. Chou that this was what had happened, how could I not go?! There was nothing to be done,” she thought, as she went on her way.

Because the matter had already come to this point, she explained the situation to the neighbor woman and asked if she could borrow a bundle of thread from their house to replace the one she had lost. After she had gone to the house, she recounted the circumstances, and explained why she needed to borrow thread. The neighbor woman took pity on the girl, but though she wished that she could be of use to the girl in such difficult circumstances, there wasn’t any ready-made thread in her house. Perhaps, she thought, she could go to Mrs. Chou in the girl’s stead and convince her to show mercy. The neighbor woman had the girl come along with her and kneel in front of Mrs. Chou. The woman explained that the girl, suffering from the beating and not knowing what to do, had said that she sold the thread to her.

“Perhaps”, she said, “the girl’s spinning was slow, and so she wasn’t able to reach her quota, or perhaps she misplaced the thread. What can she possibly do to make it reappear? If you were to spare her a beating, and beginning tomorrow she were to work harder and be more diligent in her spinning, she surely will make up for the loss.” After she had finished speaking, Mrs. Chou agreed to spare the girl from further beatings.

Then, after the neighbor woman had returned home, Mrs. Chou grabbed the girl by the hair, and angrily cursed her angrily, saying: “You lowly slave girl! You are no good at weaving thread, and even when you did manage to weave some, you stole the thread to sell it and have played all manner of dirty tricks, saying you had sold it here or there in order to get out of trouble. Then you really crossed the line by telling other people about me beating and cursing you, ruining my reputation.” Taking things a step further, she hung her from a beam, picked up a whip and beat her with it. The girl could not bear the pain, and spun around crying out, until the rope came loose on its own and she fell to the floor. She looked as if her life had already come to an end.

Mrs. Chou flung her body aside and was going to continue whipping her when she noticed that the girl’s face had changed colors. She said, “Her actions were such that she deserves to die, but I haven’t the heart to do it.” Mr. Chou then came in from outside and, seeing the situation, asked his wife what the reason for all this was. She said to her husband in an evil voice, “Because you are too indulgent, she got lazy and turned into a slacker. Every day, the amount of thread she spun was insufficient. Moreover, she secretly stole thread and sold it! She lied, saying she had sold it to our next-door neighbors, and slandered me to them. Did you truly not know about any of this? How could you love this dead thing? Her crime is deserving of death.”

Just when she had finished speaking these slanders to her husband, the girl suddenly came to. Mr. Chou’s heart could not bear her groaning and he lifted her up from where she lay, and took her back into the house. He saw that her entire body, without any interruption, was covered with wounds from the beating that had bruised and swollen such that they resembled awls.

The next day, early in the morning, the girl rose and was set to work, with Mrs Chou pointing this way and that, ordering her around. When she picked up a water bucket and went to draw water from the well, suddenly a quiet sound could be heard, seemingly from within the well, and a black cloud rose out of it and floated skyward. The heavens turned pitch black, and just then, a bolt of lightning flashed. The thunder and lightning roared seeming right on top of a cow that was in the Chou family’s courtyard. Then, with a sudden clang of thunder, a lightning bolt roared down, striking the cow right in its belly, terrifying Mr. and Mrs. Chou. They went over to look at the cow, which had already fallen to the ground and was lying there. Mixed together with the contents of its obliterated stomach was a thread that seemed to have unraveled. At this, they realized that the cow had come upon the place where the girl had left the thread that she had spun and swallowed it.

The girl’s sense of having been wronged was relieved, and she was absolved from guilt. Mrs. Chou looked as if she were trying to hide herself where she couldn’t be found. At this, Mr. Chou said to his wife, “The fault is ours. We decided to take a girl as wise as her as a daughter-in-law. At a young age, she endured every agony and worry, and never dared to talk back to you with clever arguments to explain herself! Because of her honest actions, Heaven itself released her from the rope from which she were suspended. She has even been absolved of guilt by the god of thunder and lightning and brought back to life, making manifest the wrong done to her. In this matter, how could it be but that some spirit or ghost is secretly protecting and blessing her! So, from now on, we must know the generous fortune appointed to her by fate. And from now on, we must certainly treat her with compassion, guide her well, and teach her peacefully.”

After Miss Zhou had reached fifteen sui, the marriage ceremony was concluded, and after she was married she went on to give birth to four sons and three daughters. In all matters of the house, whether big or small, general or specific, things were done in accord with the directions of Miss Zhou, and because of this nothing ever turned out poorly. From then on, the household gradually became prosperous, and two sons entered the examinations and one after another rose to become high officials. Miss Zhou reached the age of 80 without even a minor illness before her long life came to a peaceful end.

Manchu Transcription[4]

nikan i dorgi goloi bade, emu ceo halangga niyalma, eigen sargan juwe niyalma de juwe hahajui bifi, ahūngga jui de sargan gaiha bihebi, jacin jui de jeo halangga niyalmai sarganjui be hejeme toktobuha amala sarganjui i ama eme gemu jalanci aljaha ofi, sarganjui be hanci danara uksun mukūn i urse akū turgunde, tereci ceo halangga niyalma daruha urun obume gajiha bihebi,

tere fon de, sarganjui juwan ilan se, inenggidari sirge tonggo forobure de, kemun ton bi, emu inenggi i forome tucibuhe sirge i uhun sindaha ba ci waliyabufi baime baharkū turgunde, ceo halangga i sargan an i ucuri i arbun umesi oshon kiriba bihebi, tereci sarganjui be eici banuhūšame forohakūbi, embici geli hūlhame uncafi beye cisui baitalaha seme sarganjui be toome firume dabanafi moo mukšan jafafi uju dere be darkū emdubei yargiyan be tucibume ala, aika alarkū ohode uthai ergen be jocibumbi seme

cihai balai toome tandara de, sarganjui yala dosome kirici muterkū emu erin i tandara ci guweki seme bodome dalbai adaki booi mama de bufi uncabume buhe seme alaha manggi nerginde genefi amasi bederebume gaju sehe, ede sarganjui dolori gūnici, ini beye umai buhe ba akū de, ainahai gajici mutembini, tuttu seme beye emgeri uttu alara jakade, aibi geli generkū ome mutembini, arga akū genere dulimbade dolori gūnime,

baita emgeri enteke de isinaha be dahame, adaki booi mama de alafi taka cenci emu uhun i sirge be juwen gaifi orolome buki seme gūnime, adaki boode genefi baitai turgun be alafi, kemuni sirge juwen gaire baita be alaha manggi, adaki booi mama jilame gūnime, sarganjui i hafirabuha de tusa obuki seme gūnicibe ainara ini boode beleni sirge akū de, ainci sarganjui i funde genefi ceo halangga de baifi, jalgiyanjame guwebuci mutere ayoo seme gūnime, sarganjui be sasa dahalabume gamafi, ceo halangga hehe-i juleri niyakūrabufi, sarganjui-i tandara de hafirabufi arga akū adaki booi mama de bufi uncabuha seme jabuha bihebi,

gūnici sarganjui embici forohongge elhe manda ofi ton de amcabume mutehekū aise, embici geli sindaha baci waliyabuhabi aise, emgeri waliyabume akū oho be dahame ainara, bahaci tandara tūre be guwebufi cimari ci urunakū fulukan i hūsutuleme kiceme fororo ohode inu terei eden be jukibuci ombi seme baire jakade, ceo halangga hehe an i tandara be guwebuki seme alime gaiha amala,

adaki booi mama tereci beyei booi baru bederehe amala, ceo halangga hehe sarganjui i uju funiyehe ci ciyalime jafafi jilidame toome hendure gisun, sini ere fusihūn nehū sirge be sain fororakv bime, geli foroho de obume, foroho sirge be hūlhame uncafi geli hacingga demun deribume, uba tubade bufi uncabuha seme jailabume, dabanafi mini beyebe tandame tooha seme weri niyalma de algišame, mini gebu be uncambi seme, ele nememe mulu de lakiyafi šusiha jafafi tandara de, sarganjui nimere be kirici muterkū, beye emdubei torgime mihadara de, futa lakiyaha baci ini cisui multujefi na de tuheke bici, sarganjui emgeri ergen lakcaha gese oho be,

ceo halangga hehe geli ini beyebe fahaha de obufi ele nonggime šusihalame tandaki serede, tuwaci sarganjui i cira boco gūwaliyaka be sabufi, geli gisurerengge, ini yabun juken de bucere giyan, mini mujilen inu funcembi serede, ceo halangga eigen tulergi ci dosime jifi ere arbun be sabufi, sargan de turgun be fonjire de, sargan eigen i baru ehe jilgan i hendure gisun, gemu sini mujilen gosingga oho turgunde sarganjui banuhūn bulcakū be tacifi inenggidari fororo sirge be ton de amcaburkū, uttu bime geli foroho sirge be jendui hūlhame uncambime dalba adaki boode bufi uncabuha seme jailabume holtome mini gebu be ehe obume algišambi, enteke babe sini beye sarkū mujanggo, terei bucehe be ai hairara ba bi, terei weile de uthai bucere giyan seme

jing eigen i baru ehe cirai gisureme bihei sarganjui emgeri aitufi, nidume bisire be, ceo halangga i eigen mujilen de tebcirkū, deduhe baci tukiyeme ilibufi, an i booi dolo gajifi tuwaci, tandaha feye beye gubci niorome aibihangge suifun i gese si akū,

jai inenggi erde ilifi geli weile afabume hacingga ici jorišame takūrame bisire de, sarganjui hunio be jafafi, hūcin ci muke tatame gaiki sere siden gaitai aimaka hūcin i dorgici asuki tucime, sahaliyan tugi mukdeme tucifi wesihun dekdeme bihei, geli abkai boco luk seme farhūn ofi, nerginde talkiyan talkiyašame, ceo halangga booi hūwa i dolo bihe ihan i dele aimaka akjan talkiyan ebure gese kiyatar seme emgeri guwendeme holkonde akjan talkiyan i tuwa fusihūn ebunjifi ihan i hefeli be faksa darihabi, ede ceo halangga eigen sargan ambula gūwacihiyalame ihan-i hanci genefi tuwaci, ihan emgeri bucefi na de tuhefi deduhe bime, hefeli dorgi kūta efujefi dolo foroho sirge, facaha gese ofi bi, ede teni tere sarganjui i foroho sirge be, sindaha baci ihan sabufi nunggeme jeke be sahabi,

ereci sarganjui i muribuha sukdun sidarame subufi, ceo halangga hehe aimaka beyebe somire ba baharkū i gese ohobi, ede isinaha manggi, ceo halangga ini sargan i baru henduhe gisun, muse eigen sargan de ubu bifi teni enteke mergen sarganjui urun ome hesebuhebi, tere ajigan se de uthai eiten hacin-i joboro suilara be alime, gelhun akū sini baru angga karulame beyei giyan be sume faksidame yabuhakū, terei yabun unenggi de cohome abka terei lakiyaha futa be ini cisui subuhe bime, akjan talkiyan i enduri ci aname terei murishūn be subume terei ergen be aitubufi murishūn sukdun be iletulehengge, erei dolo ainahai enduri hutu i dorgideri karmame aisihangge waka seci ombini, ede uthai terei amga inenggi i hūturi ubu i jiramin be saci ombi, ereci amasi urunakū terebe jilame gosime sain i yarhūdame elhe i tacibuci ombi sehe

amala jeo halangga sarganjui tofohon se de isinaha manggi, holbon dorolon i baita be šanggabume holboho amala siran i duin hahjui ilan sarganjui ujifi, boo banjire ele amba ajige muwa narhūn baita ci aname gemu jeo halangga sarganjui i gūnin jorin be dahame yabure jakade, ele afabufi yabuha baita sain i ici ome acabuhakūngge akū, tereci boo banjirengge ulhiyen i elgiyen tumin ofi, juwe jui gemu simneme dosifi siran i amba hafan i tušan de wesifi, jeo halangga jakūnju se ofi nimeku yangšan akū elhe i jalafun dubehebi sembi,

[1] Donjina’s original text does not included story titles. This title is a translation of the title given by the editors of Donjina, Donjina i sabuha donjiha ejebun (Urumci: Sinjiyang niyalma irgen cubanše, 1989) – which gives this story the Manchu title “emu uhun sirge i murishūn.”

[2] In one common form of marriage in China, called “minor marriage” in English (as opposed to the standard “major marriage” involving two adults) and 童養媳 tongyangxi in Chinese, a family would bring in a girl, usually as a baby, and raise her as in their household as a daughter until she reached puberty, when she would marry their son. Something similar seems to be going on in this story, though Miss Zhou appears to have entered the Chou household much later than was standard in minor marriage. See Arthur Wolf and Chieh-shan Huang, Marriage and Adoption in China, 1845-1945 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1980), Ch. 6.

[3] The traditional Chinese measure of age – children were 1 sui at birth, and gained another sui at each New Year. The 13 year old Miss Zhou would been about 12 years old by Western reckoning.

[4] This transcription follows the facsimile edition of the first five volumes of Donjina found in Tong Yuquan and Tong Keli, eds, Xibozu minjian sancun qingdai manwen gudian wenxian 锡伯族民间散存清代满文古典文献 (Urumqi: Xinjiang Renmin Chubanshe, 2008), pp. 310a-312b. Paragraph divisions are given to reflect the English translation.

This story also appears in Donjina, 1989: pp. 291-298 and in Giovanni Stary, Geister, Dämonen und seltsame Tiere: Ein mandschurisches Liaozhai zhiyi aus Xinjiang (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2009), pp. 31-34 (German translation) and pp. 97-99 (Manchu transcription). In both cases there are a few minor changes from the original text, and, in addition, both are missing the final section (the final paragraph of this transcription/translation).

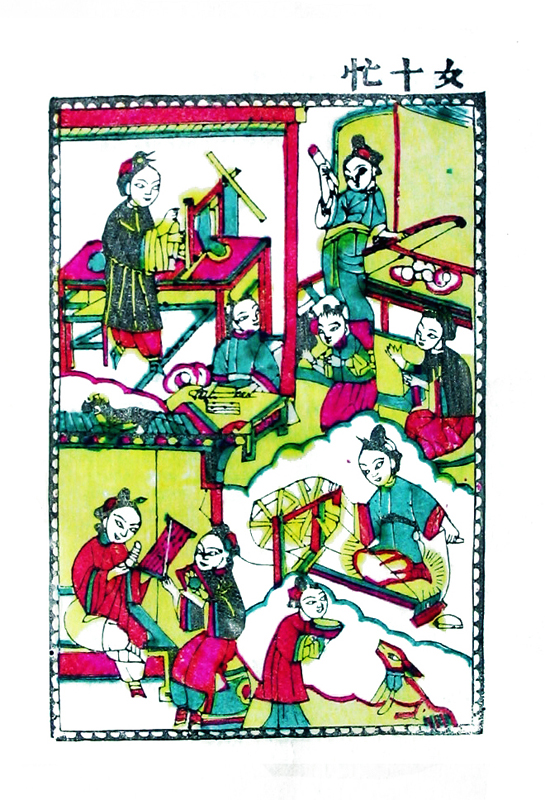

Image from

James Flath’s Online Nianhua gallery

http://history.uwo.ca/nianhua/big_cfs/cfs9.html