In this website feature, we are having Manchu Studies Group members introduce themselves, their research, and the role of Manchu in their work. If you are a member who would like to be featured, let us know at [email protected].

- Please introduce yourself briefly to the members!

I am a historian of early modern Asia who focuses on law in Qing borderlands. In 2018, I received my Ph.D. from the University of Michigan and started working as an assistant professor at the University of St. Thomas, Minnesota.

2. How did you get into Manchu? How did you learn it?

I first became interested in Manchu while thinking about my dissertation topic. When I decided on doing a comparative study of Qing borderlands, Manchu seemed like an obvious research tool. For my mandatory military service as a Korean citizen, I taught history at the Korea Military Academy from 2012 to 2015. The Research Institute of Korean Studies was just starting to offer Manchu classes, so I had an opportunity to take elementary Manchu with Kim Kyongna and intermediate Manchu with Lee Seon Ae between 2014 and 2015.

- What role does Manchu play in your professional life?

For me, Manchu mainly serves as a research tool. My current book project compares jurisdictions and boundaries in Qing-Chosŏn, Qing-Đại Việt, and Qing-Kokand borderlands, so Manchu documents have a central place in this research. Other than that, I have been using Manchu for two Twitter projects: #TodayinQing and #ManchuoftheDay. You can follow along at @JayminKim.

- Have you encountered anything memorable in Manchu-language materials, or had a memorable experience as a result of Manchu?

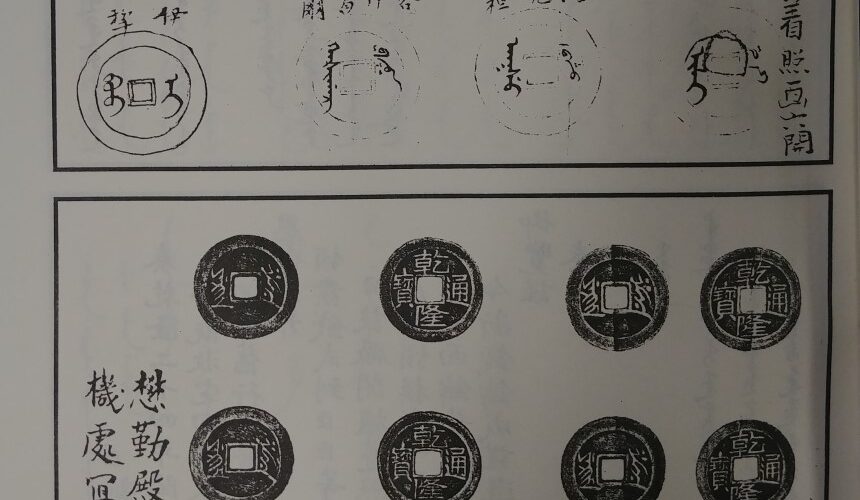

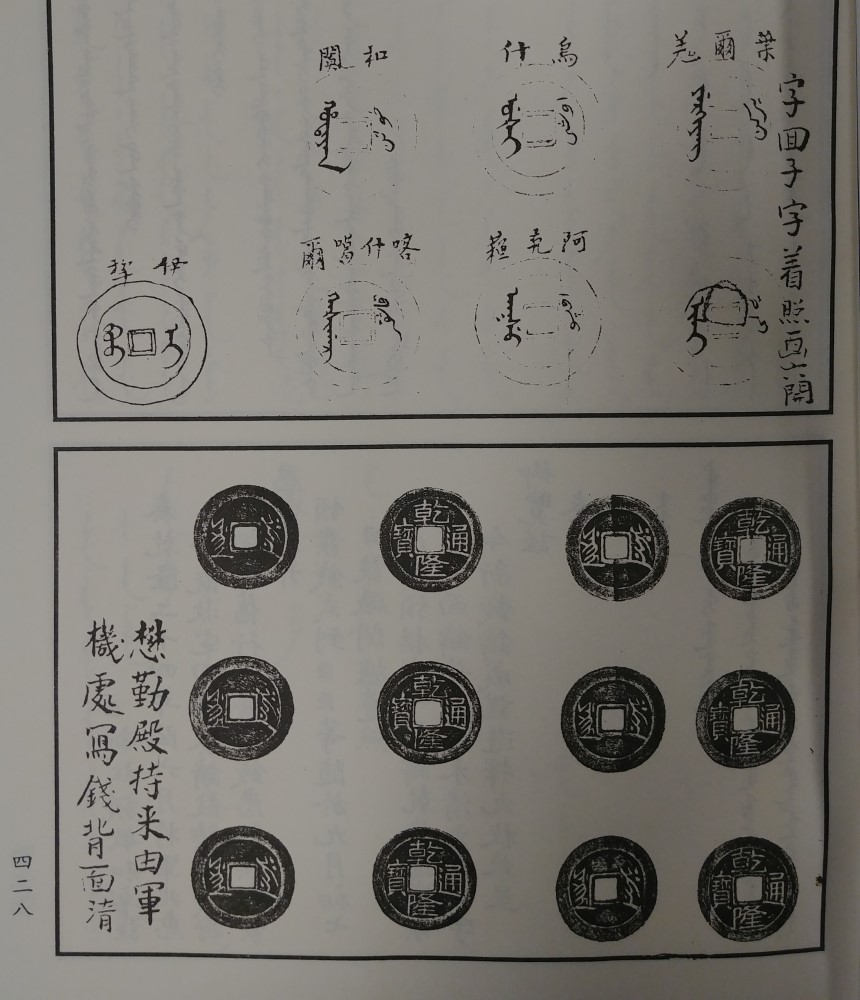

One of my favorite moments was back in May 2018. For the past year, I had been skimming through the Qingdai Xinjiang Manwen dang’an huibian 清代新疆满文档案汇编 for any materials related to Kokand and the Kirghiz. Then, a set of rubbings in one page caught my eye. They were from pūl copper coins minted during the Qianlong period and inscribed in Manchu, Chaghatay, and Chinese. It struck me as a symbol of Qing Xinjiang with all its boundaries and bridges: ruled by the Manchu amban and soldiers, inhabited by Turkic speakers sharing ties with other Central Asians, and simultaneously separated from and connected to China Proper.

- What future projects related to Manchu are you envisioning? Do you have any plans for collaboration?

While doing research on my current project, I have encountered many Manchu-language materials on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Central Asia that have not yet been widely studied. I would like to collaborate with early modern Central Asianists for an annotated translation of some of these documents.

6. What is your favorite Manchu word? Why?

This is a tough one, but I would have to go with hūlhambi. I like how versatile the verb is, since it usually means to steal but also can refer to anything that is done furtively (and most likely illegally). Since my research focuses on illicit activities, I also encounter it in a lot of my documents.

7. Is there anything else you’d like to say to the members?

Our field has been growing globally in the past few decades. As secretary, I would like to act as a liaison between the Manchu Studies Group and the global community of Manchu scholars.

From my own experience, I know that interest in Manchu has grown exponentially in Korea in the past decade or so. And yet, not much of the Korean scholarship on Manchu is known outside Korea. I would love to learn more about similar developments in other parts of the world. So please let me know what has been going on in your own community of Manchu scholars!