In this website feature, we are having Manchu Studies Group members introduce themselves, their research, and the role of Manchu in their work. If you are a member who would like to be featured, let us know at [email protected].

- Please introduce yourself briefly to the members!

I am a historian of Qing and Republican China interested in identity, empire, language and the state. I also try to think about the Qing in global and comparative terms – my current book project deals with the Qing banners as a “service elite” akin to the Japanese samurai, imperial Russian service nobility, and Ottoman janissaries. I received my PhD from Harvard in 2018 and am currently a postdoctoral associate at Yale’s Council on East Asian Studies.

2. How did you get into Manchu? How did you learn it?

I actually had worked on Manchu people prior to learning the language – as an undergraduate, I wrote a senior thesis on ideas about nationalism and Chinese identity among a group of Manchu students in Japan in the early 20th century. When I got to grad school, I knew I wanted to keep working on issues related to Manchu (this was a big part of why I went to Harvard; it’s one of the few places where Manchu instruction is consistently available) and so I took the two year Manchu sequence, first with He Bian (the current MSG president) and then with Mark Elliott.

3. What role does Manchu play in your professional life?

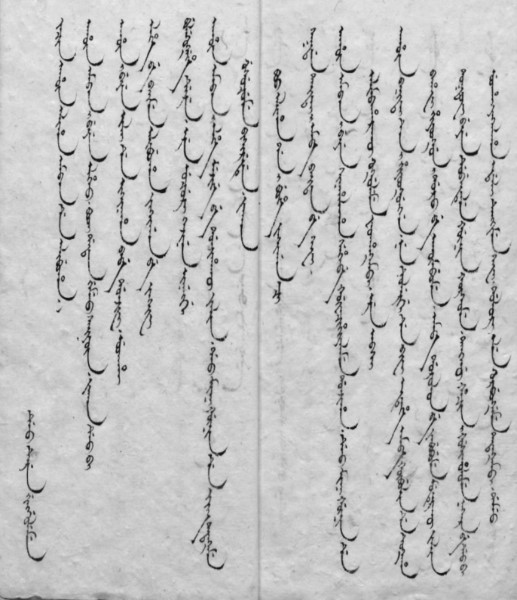

Manchu is really central to my research and to other parts of my professional life as well. I have published a couple of articles based around the study of Manchu – one on the early 20th century Daur writer Donjina and his experience of Manchu identity in late Qing Ili, and one on Manchu language education among Han bannermen in the 18th and 19th centuries. For my current project, probably about half my sources are in Manchu.

I’ve also done a lot with teaching Manchu. I taught first-year Manchu at Harvard in 2016-2017, and then taught Manchu online in the summer of 2020 to interested students and scholars from around the world. The online course was a really rewarding experience, as it helped offer many people the opportunity to take a Manchu class who wouldn’t otherwise have had access to the training. I have since shared the teaching materials I used for the class (mostly created when I taught at Harvard) here. The online class also led me to meet a linguist and descendant of Qing banner people who took the class and then created some great new tools for typing in Manchu script. I certainly hope to teach Manchu this way again.

4. Have you encountered anything memorable in Manchu-language materials, or had a memorable experience as a result of Manchu?

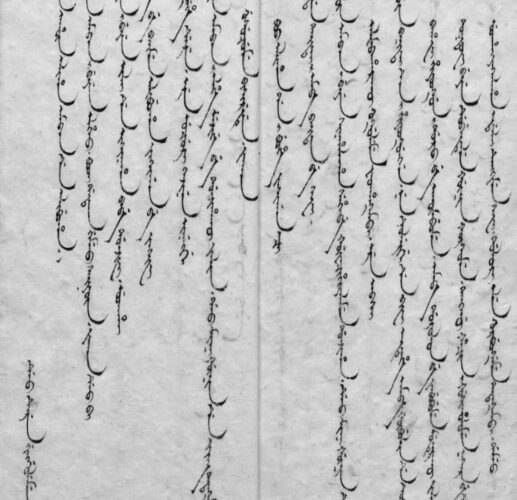

I’ve found tons of cool stories in Manchu documents. I’ve written about a few of them at length elsewhere, including the story of some Russians captured along the border in Xinjiang who tried to escape from the Guangzhou banner garrison (where they were sent after their capture) and the story of how the Qianlong emperor made changed a Manchu official’s name to Nikan Fusihūn (meaning something like “Beneath a Han,” or, less literally “Stinking Han”) because he thought his real name sounded too Chinese.

.

5. What future projects related to Manchu are you envisioning? Do you have any plans for collaboration?

I’ve been thinking that my next major project will be focused on translation and the Qing state. One thing that is perhaps a bit surprising about the Qing government is just how many high officials began their careers as translators. That is to say, translation wasn’t just a routine bureaucratic task, it was seen as a part of the career path, particularly for officials who ended up serving on the frontier. Yet it’s a career path and a set of practices that we know far less about than we do about the civil examinations and the study of classical texts, which have always been seen as the normative route into government. So I want to study translators, what they were doing (that is, how translation worked), and how their work fit into the structure of the state.

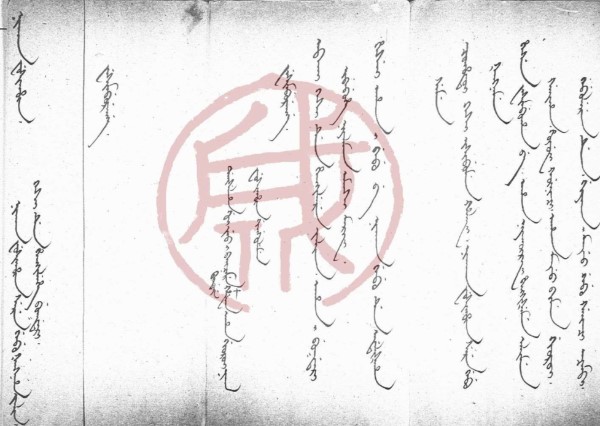

One very cool Manjuristic connection for all this (in addition to the fact that translation involving Manchu was the bulk of translation work) is that the bureaucratic use of Manchu led to much of the literary use of the language. I’ve (in collaboration with Mark Elliott, Devin Fitzgerald, and others) translated a series of letters by the Mongol banner official Tsebak from c. 1800 that show that he was writing to men like Sungyūn, author of the Tales of 120 Old Men (Emu tanggū orin sakda-i gisun sarkiyan), in Manchu, with the whole network seemingly connected by their service in the translation bureaucracy in Beijing early in their careers. It is really fascinating to realize that the supposed decline of Manchu into being nothing more than a bureaucratic language maybe gets it all wrong: it was people who learned Manchu to be bureaucrats who produced some of the most enduring work in the language.

.

6. What is your favorite Manchu word? Why?

Niyamniyambi – This is one of the first Manchu words I learned, prior to studying the language formally. I love that this word, which is so common in the documents I read, describes an activity that requires multiple words to express in English (and most other languages) – “shooting from horseback.” And I think that the sound is great; the repetitive niyam-niyam gives you almost this onomatopoetic sense of someone bouncing on horseback as he tries to aim his bow.

7. Is there anything else you’d like to say to the members?

As you may have noticed, three of the four profiles we’ve put out so far have been of members of the MSG board. This isn’t because we’re self-promotional (at least, it’s not meant to be!). We would really love to share the work of many more Manjurists – so please get in touch if you’d be willing to participate. It doesn’t matter what career stage you’re in – grad students, postdocs, independent scholars, faculty, or if you’re not in academia at all. If you work with Manchu, we want to hear from you!