Jack Rabinovitch

Jack Rabinovitch is a PhD student in the Department of Linguistics at Harvard University with a special interest in Manchu language. His research focuses on cross-linguistic approaches to perspective and attitude embedding.

Regardless of the language they speak, people across the world tend to be intent on telling others what they know – and often what they do not know; in writing this blog post, I am no exception. For Manchu speakers seeking to explain what they know, the most common word used to express knowledge (or lack thereof) is the verb sambi. In this blog post, I will cover some of the linguistic intricacies of sambi, including the kinds of structures that can be embedded under it and how Manchu speakers express that they know (or do not know) things. Later I will compare sambi to the English verb “know” and the Chinese word zhidao 知道.

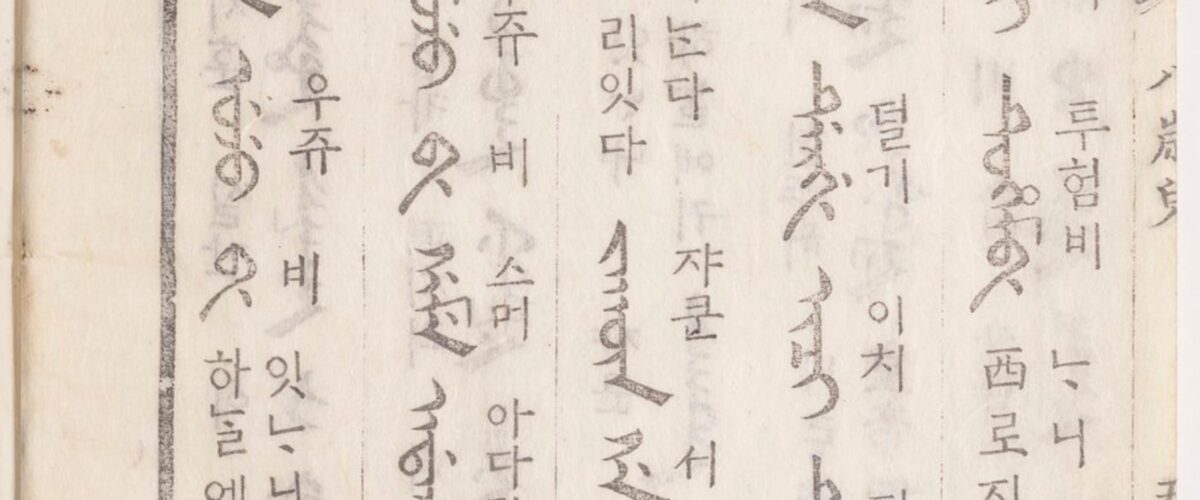

In linguistic terms, the things that are “known,” and their linguistic structures, are called the complements of the verb they attach to. Below, I will denote the complements of sambi in brackets. All data were collected via Manc.hu’s online Concordance, where I searched for sambi and its various inflections.

PART I: Embedding Nouns and Pronouns

The simplest examples of embedding under sambi are in the forms of nouns, which typically take the accusative case (be). In these instances, sambi can refer to a general familiarity with something or someone:

(1)

maise hadure haha [mangga jugūn be] sahaThe man who reaps wheat has known [the difficult road]. (Song of our Land)

(2)

age, si [mimbe] sarangge, bi emu gabula niyalma

Sir, what you know [of me], is that I am a glutton.

(Manchu Q and A in Forty Sections – Meyen 18)

Additionally, sambi can indicate that one knows the identity of something (e.g., what a god’s name is, or which children are truly filial):

(3)

[da weceku i gebu hala be] saman niyalma beye sambi

The shaman himself knows [the head household god’s name and clan] .

(N. N. Krotkov’s Questionnaire to Balishan Concerning Sibe-Solon Shamanism)

(4)

boo yadahūn ohode [hiyoošungga jui be] sambi

If the home becomes poor, [the filial child] will be known.

(Sentences, Maximes et Proverbs Mantchoux et Mongols)

As can be seen by the statement from (3), the complement need not be directly adjacent to the verb; the subject may even intervene between the two. Though rarer, when the complement of sambi is a noun, it need not be marked as accusative:

(5)

[sini beye mujin i dolo] inu getuken i sambi

You clearly know [the inside of your own intentions].

(Tale of the Nisan Shamaness – 18)

In addition to people, places, and the identities of things, the most common thing that one may say that they know are facts, or truths about the world. When referring to specific facts with nouns, the word baita is often used. Otherwise one may simply use a pronoun.

(6)

[julgei utala baita be] saci ombi

One should know [various matters of antiquity] .

(Tales of the 120 Old Men – Debtelin 05 Tale 11)

(7)

[ere be] bi inu sambi

I also know [this].

(Nogeoldae, Lao Qida – 02)

(8)

[aibe] sambi

[What] do I know?

(Tale of the Nisan Shamaness – 06)

PART II: Embedding Verb Phrases

Of course, referring to a fact by a noun or pronoun will only get you so far. When one wants to express that they know something, they usually want to embed more than a noun. In Manchu, this is most commonly done through nominalizing a participial phrase. In this case, the participle (ending in -ha/he/ho/ka/ke/ko or -ra/re/ro) will take accusative case:

(9)

teni [ini saciha šulhe mooi cikten, uthai ere jaka ojoro be] sahabi

Only then did he know [that the trunk of the pear tree which he cut was in fact this thing] .

(Strange Tales of Liaozhai – fascicle 01)

(10)

[tubai dulin niyalma be gamaha be] sarkū

They did not know [that half the people there had been moved] .

(Old Manchu Chronicles – Nurhaci (1607-1626) – Manbun Rōtō – Nurhaci – 05-41)

(11)

bi [geren saikan i uttu ohongge be] aide sambini

How do I know [that everything beautiful is so much like this] ?

(Von Zach’s The Daodejing – Dao – Doro 21)

The use of participial form is additionally used with the copula bi, as we see in (12) with the imperfective participle form of bi, bisire:

(12)

teni [juwe hojo faha uhei emu yasai hūntahan de bisire be] saha

He then knew [that the two pupils had come together in one eye socket] .

(Strange Tales of Liaozhai – fascicle 01)

When used rhetorically, sambi can refer to some fact that has not yet been introduced to the conversation. In these cases, the fact is quickly explained in the following sentence, which I denote through curly brackets. These are not syntactically complements, though they are the “thing being known”:

(13)

we saha {abka gukubure jakade gūnihakū mini erin jalgan isinjire jakade, dere acame muterakū oho, yasa tuwahai aldasi bucembi}

Who knew? {Because of Heaven’s destruction, unexpectedly my destiny has come and I will not be able to meet you face to face, before your eyes I am dying young.}

(Tale of the Nisan Shamaness – 01)

(14)

bayan agu si adarame sarkū nio, {ere baci goro akū nisihai birai dalin de tehe teteke gebungge hehe saman bi}

Rich sir, how do you not know? {Not far from here, staying by the shore of the Nisihai river, there is a shamaness named Teteke.}

(Tale of the Nisan Shamaness – 05)

PART III: Converbs

Typically, imperfective converbs, ending in –me, which precede sambi, denote the manner in which one knows a piece of information. These are not the complements of the verb, but rather a sort of adverbial addition to the verbs:

(15)

nikan bithe be hūlaha manggi urunakū [oyonggo jorin be] hafukiyame safi …

After the Chinese book was read, [the important aims] were known in detail …

(Tales of the 120 Old Men – Debtelin 05 Tale 01)

(16)

[niyalmai arbun bisire beye, arbun akū fayanggai geren turgun be] akūmbume hafume sara de isinaci …

If one gets to the point of knowing exhaustively and thoroughly [the common logic of people’s form-having bodies and formless soul] …

(A Complete Anatomy in Manchu – 01 Niyalmai banin beyebe šošome gisurehengge)

Perfective converbs, ending in -fi/pi/mpi, seem to consistently act as adverbials and not as complements. They denote the reasons for one gaining (or lacking) knowledge:

(17)

ememungge banitai sambi ememungge tacifi sambi

Some were naturally endowed with the knowledge, some knew it through study.

(Tales of the 120 Old Men – Debtelin 05 Tale 04)

(18)

dain dosika ergi sucungga tai niyalma dulbadafi sarkū

The people on the first platform on the side where the troops entered were acting carelessly and thus did not know.

(Old Manchu Chronicles – Nurhaci (1607-1626) – Manbun rōtō – Nurhaci – 04-29)

Among the perfective converbs the compound bahafi sambi meaning “to comprehend” or simply “to know” can be found extensively. It is also found in the set phrases adarame bahafi sambi, aide bahafi sambi, and ainambahafi sambi, all meaning “how do (you) know?”:

(19)

han inu bahafi sarkū kai

Even the Khan didn’t know.

(Old Manchu Chronicles – Nurhaci (1607-1626) – Manbun Rōtō – Nurhaci – 09-71)

However, it does seem that there are some cases where the converb is part of the complement rather than an adverbial; this is seen with the imperfective converb -me:

(20)

irgen [jobome] sarkū

The people do not know [of suffering] . (Chinese: 民不知勞)

(Copied text of a Stele from the Ili region)

This kind of complement differs from the nominalizations we saw in Part II, in that the complement jobome does not denote a fact, something that is true, but rather a kind of experience that can be known or experienced. In the nominalizations we saw in Part II, one can easily translate into the English using “that”, while these kinds of experiences require a gerund (of suffering) or an infinitive (to suffer).

(21)

I know that I suffered.

Implies: I suffered.

I forgot that I put my clothes in the drier.

Implies: I put my clothes in the drier.

(22)

I know (what it is like) to suffer.

Does not imply: I suffered.

I know to put my clothes in the drier.

Does not imply: I put my clothes in the drier.

English and Manchu seemingly both consider “know” to have this double life as denoting both holding knowledge of facts (things that are true) as shown in (21), and as denoting being familiar with a particular kind of experience (22). While the former is factive, the complements are implied to be true by the speaker, the latter is not. Both languages distinguish these two meanings not in the verb that they employ, but rather the kind of complement. English “that” and Manchu nominalization are used to embed knowledge of facts, and English gerund/infinitive and Manchu converbial -me are used to embed familiarity with an experience.

This pattern that English and Manchu both differentiate facts and experiences by the kind of complement that is embedded is a small part of what Wurmbrand & Lohninger (2019) call the Implicational Complementation Hierarchy (ICH), where across languages, multiple strategies are utilized as ways of embedding different kinds of complements. I leave it up to future work to figure out the details of how nominalizations and -me converb complements differ in their distribution, use, and meaning, but it seems promising that so far they seem to have a distribution which matches that of Wurmbrand & Lohninger’s typology.

PART IV: Embedding Questions

Questions can be embedded under sambi as well. In these cases, like English and Chinese, these mean something along the lines of “I know whether …” or “I know what …” These are often called “indirect questions” in pedagogical literature, as they are not being directly asked by the speaker, but rather represent some piece of knowledge which is known. For a Manchu construction, this is done through the addition of the accusative marker to a question denoting adjective, such as antaka, or through the addition of the accusative to a participle, which in the case of yes/no questions, may be in the X-not-X form (bisire akū). This is extremely similar to the Chinese, particularly the X-not-X construction (是否), which I have included along with the Manchu to show its similarities:

(23)

[ama i gūnin de antaka be] sarkū

我不知道 [我父親怎麼想] 。

I do not know [how my father feels (about it)] .

(Tale of the Nisan Shamaness – 01)

Interestingly, nominalized non-questions and nominalized questions seem to be able to act together as the complement of sambi, as seen in this interesting line from the Tale of the Nisan Shamaness, where sere anggala combines two complements, giving a “not only x, but also y” meaning. Note that while the English has two “knows,” the Manchu only contains one sarkū (the negative form of sambi):

(25)

[niyalma be weijubure] sere anggala [ini beye hono ya inenggi ai erinde bucere be] gemu sarkū

They not only don’t know [of bringing a person back to life], they also don’t know [what day and what time they will die] !

(Tale of the Nisan Shamaness – 05)

However, throughout the Manc.hu corpus, I did not find a sentence-final question particle (o, ni or –n) embedded under sambi in Manchu. Interestingly, this is an unsurprising fact, given what we know about other languages. If we take a look at Chinese, the X-not-X form verbs can be embedded under zhidao 知道, just as in Manchu (with 是否 or 是不是 instead of bisire akū). However, the analogues to Manchu o, ni, and –n, namely ma 嗎 and ne 呢, cannot be embedded under “know” zhidao 知道:

(26)

我知道 [他來不來] 。

But not:

*我知道 [他來嗎] 。

English also acts similarly, where questions embedded under “know” act slightly differently, and do not cause subject-auxiliary inversion like they do when not embedded:

(27)

I know [when he came] .

But not:

*I know [when did he come] .

This is not to say that these kinds of “full” questions, as Suñer (1993) would call them, cannot be embedded; they are embedded all the time under verbs of saying and thinking, just like quotations in Chinese and English. I show these below with o, ni, and –n in saiyūn; note that these examples use seme, a requirement of embedding finite forms:

(28)

labtai [si mini loho be alime gaime mutereo] seme henduhe

labtai 說:[你會接受我的劍嗎?]

Labtai said, [“Can you receive my sword?”]

(Old Manchu Chronicles – Nurhaci (1607-1626) – Manbun Rōtō – Nurhaci – 01-02)

(29)

[mini elcin be waha ni] seme gūnimbi dere

想到:[我的信使被殺了嗎?]

I thought, [had my messenger been killed?]

(Old Manchu Chronicles – Nurhaci (1607-1626) – Manbun Rōtō – Nurhaci – 03-15)

(30)

genggiyen han, [geren beise gemu saiyūn] seme fonjiha

文皇帝問:[太子都好嗎?]

The Brilliant Khan asked: [How are all the princes?]

(Old Manchu Chronicles – Nurhaci (1607-1626) – Manbun Rōtō – Nurhaci – 02-11)

PART IV: A Small Puzzle

A small puzzle comes from Eight Year Old Child, a Manchu-Korean text from 1777. Here, there are instances where sambi embeds a finite verbal form, that is, a phrase ending with –mbi or the bare copula bi. Like all finite verbal form embedding in Manchu, this is done with the help of the auxiliary converb seme. I show it here in (31) and (32):

(31)

han fonjime hendume [uju bi seme] adarame sambi

The Emperor asked: “How do you know {to say} [that (the sky) has a head] ?”

(Eight Year Old Child)

(32)

tuttu ofi [uju bi seme] saha

Because of this, I know {to say} [that (the sky) has a head] .

(Eight Year Old Child)

It is not clear from the Korean whether the meaning of this sentence is that of an attitude complement, “know that the sky has a head” where seme acts purely as an embedder, or if it is an irrealis complement, “know to say that the sky has a head” where the seme has its literal meaning of “say”. From the context, it would seem that an attitude complement would work best, however, embedding under seme includes a finite form, which, like the question particles o, ni, and nio, is often thought to contribute to a speech act, and thus should not be embeddable under “know”, which cannot take a quote in English or Korean. While an irrealis interpretation bypasses this by having seme itself be the complement, this kind of language is only seen in Eight Year Old Child in the entire manc.hu corpus, and including the “say” meaning would be awkward. I leave this puzzle as an exercise for future work.

Despite the vast historical and typological differences between Manchu, Chinese, and English, these languages all share something in common: embedding questions under “know” are restricted to certain constructions, and not others, and among those constructions, there is a clear divide between the complements which denote knowledge of a fact and complements which denote familiarity with an experience. Most striking is that Manchu and Chinese both have an option of using question final particles or using X-not-X constructions, and that in both cases, the latter is permissible under “know”, while the former is restricted to either full sentences, or embedding under “say” or “think.” In this way, the Manchu language not only provides a window into Manchu culture and Qing history, but also into the number of ways that language may vary, as well as the similarities that they all share.

References

Sam-Sin, Fresco, and Léon Rodenburg. Manc.hu, 2020, manc.hu/.

Suñer, Margarita. “About indirect questions and semi-questions.” Linguistics and Philosophy 16.1 (1993): 45-77.

Wurmbrand, Susi. and Magdalena Lohninger. ‘An implicational universal in complementation—Theoretical insights and empirical progress’, Propositional Arguments in Cross-Linguistic Research: Theoretical and Empirical Issues. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Edited by J. M. Hartmann and A. Wöllstein. (2019)