Chenyu Tu (涂辰宇)

Chenyu Tu 涂辰宇 is a PhD student in the Department of Comparative Literature at Brown University. He works primarily on early modern European literature and is also interested in the Sino-European interface of this period, in which the Manchu language played an important role.

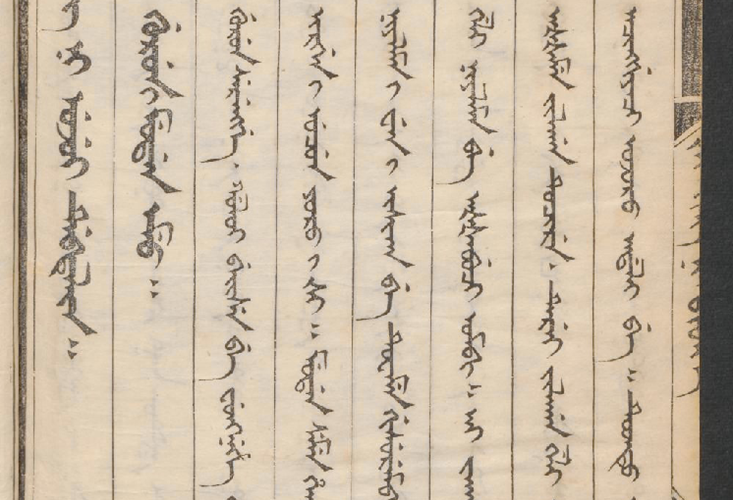

This blog post aims to identify the source text of Ši ging ni bithe (1654), the earliest Manchu translation of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing 詩經). The work was formally commissioned by the Shunzhi emperor, who wrote a Manchu preface to it (Figure 1). The text is in Manchu only, and does not give interlinear notes or parallel texts in Chinese. The edition consists of twenty juan in stitched binding. The block has double borders, black mouth, and double black fish tails; the block center gives the book title in Manchu script.

In her paper on the Manchu versions of the Shijing, Xu Li, a researcher at the First Historical Archives in Beijing, discusses the 1654 translation, which she says survives in both ten-volume and twenty-volume editions. The version in the First Historical Archives (presumably the edition from which she quotes), is in twenty volumes, as is the version at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, from which I will be quoting (which is missing juan 11-20). As the quotations in Xu’s paper are identical to the corresponding texts in the Berlin version, it is safe to assume that we are working from the same edition.

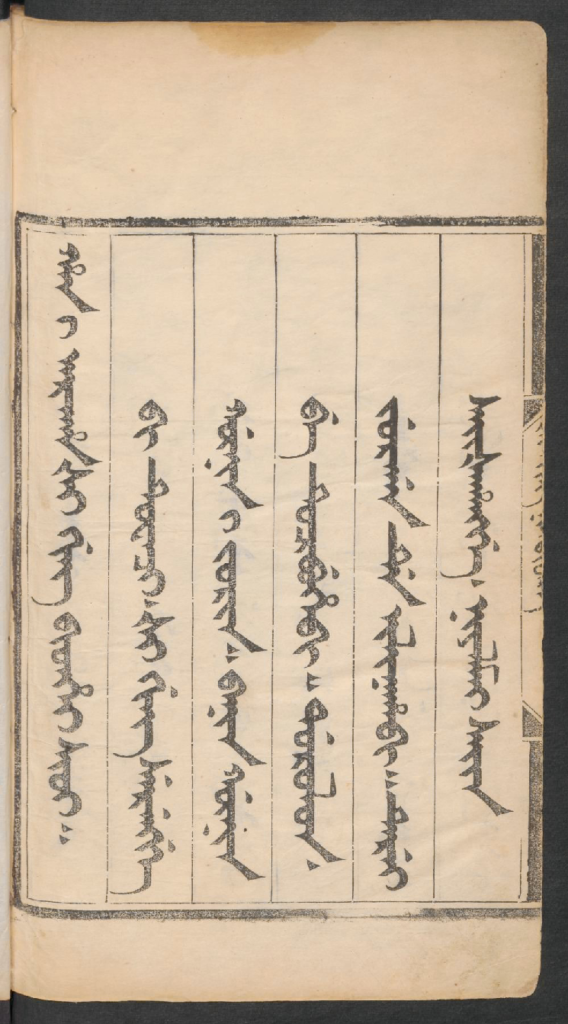

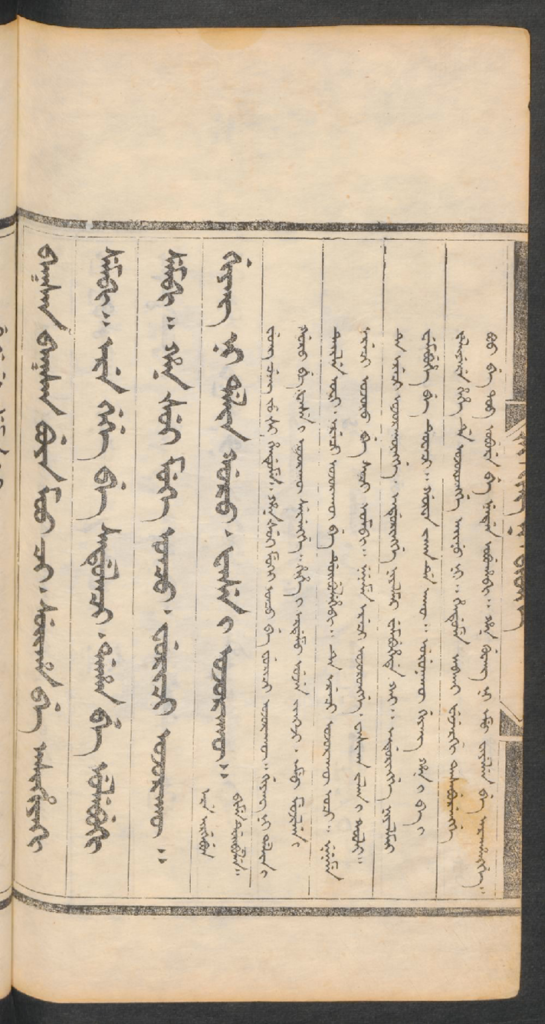

The 1654 Manchu Shijing is an annotated translation, as Xu notes: “This edition consists of two parts: the main text and the collected commentary. The main text is in a larger font in thick brush strokes, while the commentary is in a smaller font in thinner strokes” (50). For this reason, the source text (or one of the source texts) of this translation should probably be a Chinese commentary on Shijing, most likely the Collected Commentary (詩集傳 ca. 1177) composed by Zhu Xi (1130-1200), which has been influential for over eight hundred years. It is this text that Xu identifies as the source of the Manchu translation and commentary. To back up this claim, she transcribes the beginning passage of the main text from the Manchu, a commentary on Shijing’s first section, the gurun-i mudan (i.e., Guo feng 國風), which reads: gurun i mudan emu.. gurun serengge. goloi beise be fungnehe ba.. mudan serengge irgen i ucun yoro i s̆i. (Figure 2). A literal translation would be: “Songs of the states, one. ‘State’ refers to the lands with which feudal lords are enfeoffed. ‘Song’ means the poetry of the ballads and rumors of the people.” This passage is clearly a translation from Zhu’s commentary (國者,諸侯所封之域;而風者,民俗歌謠之詩). The translation is awkwardly literal and slavish to the Chinese syntax, as is evidenced by the (mis-)translation of Chinese geyao (歌謠) as ucun yoro (“ballads and rumors”). This literal faithfulness will help when we later come to decide on the source text among multiple similar texts. But let us first see whether the source text is Zhu’s Collected Commentary.

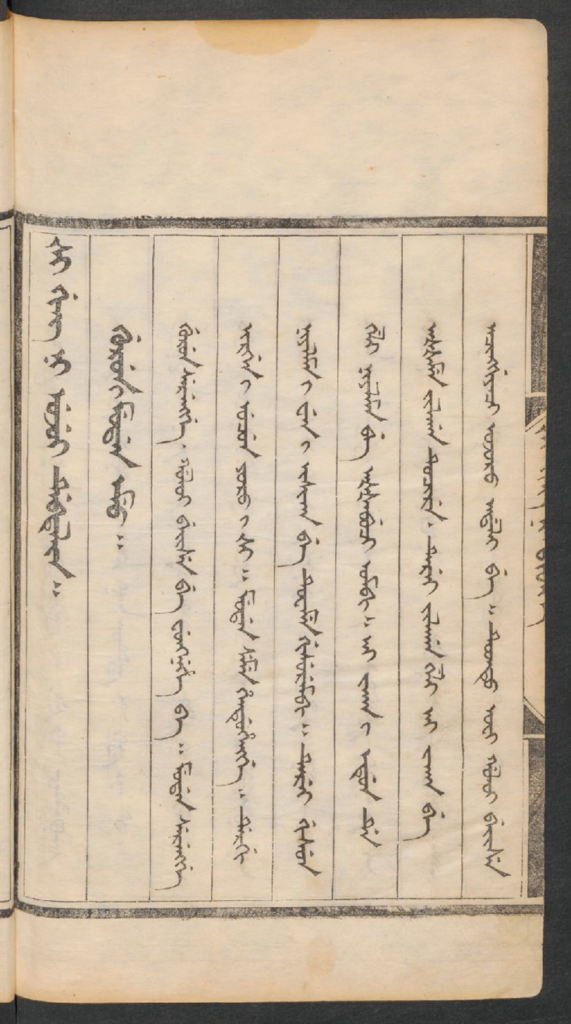

The translation has two parts: the main text in a larger font and the commentary in a smaller font. But there is yet another commentary in an even smaller font, which, for instance, appears at the end of Ode 4 (Jiu mu 樛木) (Figure 3). Here is the first stanza in Chinese, Manchu, and English:

Ch. 南有樛木,葛藟纍之。樂只君子,福履綏之。

Ma. Julergi lasari moo de hūs̆a siren fasimbi.. buyecuke ambasa saisa de. hūturi fengs̆en isimbi..

En. In the South there are trees with down-curving branches, the ko creepers and lei creepers cling round them; joyous be the lord, may felicity and dignity give him peace.

(Karlgren’s translation of the Chinese)

In his peculiar way, Zhu interprets the “lord” (Ch. junzi; Ma. ambasa saisa) as a “lady” – Tai Si (太姒), wife of King Wen – and reads the poem as being in praise of the queen. The Manchu commentary translates Zhu’s definition of the lord as follows: ambasa saisa serengge. geren hehesi ho fei be tukiyeme hūlahangge (“’Great lord’ was [how] the many concubines called the queen in praise”). Zhu’s commentary reads: 君子,自衆妾而指后妃). The Manchu commentary ends with a passage that is in line with Zhu’s interpretation, but not found in his Collected Commentary:

dung lai lioi s̆i hendume.. han gurun i juwe joo. sui gurun i du gu.. tang gurun i u ho.. gurun be gukubume jobolon obuci.. jio mu fiyelen i ho fei be s̆i bithe i niyalma. adarame s̆umin sais̆ame dahūn dahūn i nasarakū ni..

Mister Lü of Donglai says: “As the two Zhaos of the Han [dynasty], Dugu of the Sui, and Empress Wu of the Tang caused troubles in such a way as to destroy the country, how can the poet not highly praise and feel endless regret for the queen in the poem ‘Jiu-mu’?”

The two Zhaos, Dugu, and Wu are all empresses (or concubine of the emperor) in Chinese history who, according to the commentator, brought disaster to their respective dynasties. The commentator is Lü Zuqian (呂祖謙 1137-1181), a close friend of Zhu’s, also known by the name of his ancestral prefecture, Donglai (東萊). His commentary agrees with Zhu’s interpretation of the lord as “lady,” but the quotation itself is not found in the editions of Zhu’s Collected Commentary that I have seen.

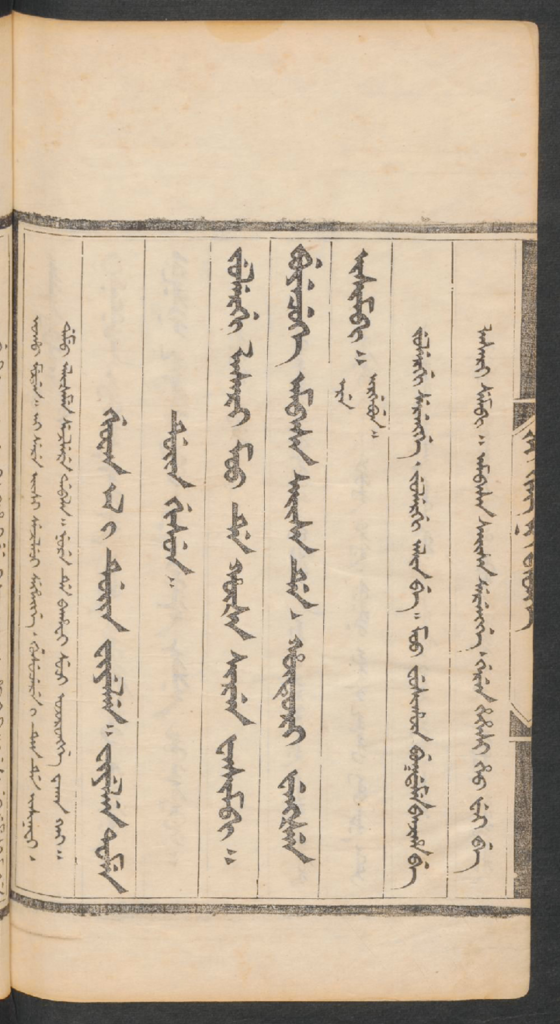

At the end of Ode 9 (Han guang 漢廣) (Figure 4), there is another commentary in a font smaller than that for the regular annotation, much longer than the previous example and not from Zhu’s contemporaries. The beginning reads:

fung ceng ju s̆i hendume.. han s̆ui mukei onco be furici ojorakū.. giyang ni dalin i goro be fase i ojorakū serengge.. hehe i erdemu ujen jingji. emu mujilen i teile ofi. ereci ojorakū be duibulehebi..

Mister Zhu of Fengcheng says: “One should not swim in the broad Han river; one should not take a raft to the distant shore of the Yangtze River. That is meant figuratively to say that the respectful and dignified virtue of women with full commitment is not to be hoped for.

This is a reading of two lines from the poem: 漢之廣矣,不可詠思。江之永矣,不可方思 (“The broad expanse of the Han, it cannot be waded across; the long course of the Kiang, it cannot be passed by raft” [Karlgren]). But the “Mister Zhu of Fengcheng” referred to here can only be the commentator Zhu Shan (朱善 1340-1413), from the early Ming period, who surely could not have appeared in Zhu Xi’s twelfth-century commentary. Therefore, we can conclude that at least one of the source texts for the Manchu translation must be later than the early Ming and that the translator probably worked from an edition of Shijing with collected commentaries that incorporated into Zhu’s text other major contributions to Shijing scholarship. But which edition?

Three major achievements in the Shijing commentarial tradition come to mind: Liu Jin’s (劉瑾 ca. 1310-60) Shizhuan tongshi (詩傳通釋), Zhu Gongqian’s (朱公遷 fl. 1341) Shijing shuyi huitong (詩經疏義), and Hu Guang’s (胡廣 1369-1418) Shizhuan daquan (詩傳大全). The commentary quoted above about Ode 4 appears in all three texts:

Liu Jin, Shizhuan tongshi, 1.4: 吕東萊曰:漢之二趙、隋之獨孤、唐之武后,禍至亡國。樛木后妃,詩人安得不深嘉而屢嘆之乎。

Zhu Gongqian, Shijing shuyi, 1.4吕氏曰:漢之二趙、隋之獨孤……

Hu Guang, Shizhuan daquan, 1.4: 東萊吕氏曰:漢之二趙、隋之獨孤……

The quotation is the same in the three texts, but the commentator is referred to in different ways – as “Lü Donglai,” “Mister Lü,” and “Mister Lü of Donglai.” The Manchu translator, who stays strictly faithful to the literal, agrees with Hu Guang’s Shizhuan daquan in calling the commentator dung lai lioi s̆i (Ch. dong lai lü shi).

The commentary on Ode 9 quoted earlier appears in Shijing shuyi and Shizhuan daquan:

Zhu Gongqian, Shijing shuyi, 1.9: 《輯録解頥》曰:漢之廣者不可泳,江之永者不可方,以比女德之端莊靜一者不可求也。

Hu Guang, Shizhuan daquan, 1.9: 豐城朱氏曰:漢之廣者不可泳……

Again, the translator agrees with Shizhuan daquan in referring to the commentator as fung ceng ju s̆i (Ch. feng cheng zhu shi). Further comparison suggests that the source text of the Manchu translation is most probably the imperially-commissioned Shizhuan daquan (Complete Commentary on the Classic of Poetry), part of the early fifteenth-century magnum opus entitled Complete Commentaries on the Five Classics (五經大全 Wujing daquan). This edition of Shijing is indeed based on Zhu’s influential commentary. This explains why the Shunzhi translation of the Shijing, though mostly based on Zhu’s commentary, includes quotations from commentators not found in Zhu, such as we find in Hu Guang’s edition.

Based on this finding, we may conclude that the Manchu translators of Chinese classics did not translate from what we now consider to be standard commentaries. They were working in a specific historical period from a concrete set of texts in the commentarial tradition that had come down to them. The 1654 translation of Shijing, done in the first years of the Qing reign and long before the dynasty made its own official commentaries on the classics in the mid-eighteenth century, thus worked from the standard text of the previous dynasty. Further examination would show that the Manchu translator(s) had considerable difficulty understanding and translating the commentary: sometimes they translated it word by word without making much sense; sometimes they misunderstood the syntax of the commentary; sometimes they correctly translated the annotation but misrendered the corresponding words in the classical text. These mistakes and inaccuracies left their traces in turn on the Latin translation of Shijing by the Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Lacharme 孫璋 (1695-1767); this text, incidentally, later made its way into the hands of Ezra Pound. The many errors and awkward phrasings in the 1654 Manchu text were corrected in the 1768 Manchu translation of the Shijing, published a year after Lacharme’s death. This was decades after the Qing had created its own standard collected commentaries – a new exegetical tradition in which we may assume that the Manchu translators working in the reign of the Qianlong emperor were steeped, and which guided them in producing a more accurate version of this classic text.

References

- Cheadle, Mary Paterson. Ezra Pound’s Confucian Translations. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

- Durrant, Stephen. “Manchu Translations of Chou Dynasty Texts.” Early China 3 (1977): 52-4.

- von der Gabelentz, Hans. Sse-schu, Schu-king, Schi-king in mandschuischer Übersetzung: mit einem Mandschu-Deutschen Wörterbuch. Leipzig: 1864.

- Karlgren, Bernhard. “The Book of Odes, Kuo feng and Siao ya.” Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 16 (1944): 171-256.

- Xu Li徐莉. “Qingdai Manwen Shijing yiben ji qi liuchuan” 清代滿文詩經譯本及其流傳. Minzu fanyi 3 (2009): 50-5, 96.

- Yang Jinlong楊晉龍. “Shizhuan daquan yu Qingdai qianqi shijingxue guanlianxing tantao” 詩傳大全與清代前期詩經學關聯性探論. Zhongguo wenzhe yanjiu jikan 48 (2016): 97-138.

- Zhang Hui張輝. “Zhu Xi shijizhuan xu lunshuo” 朱熹詩集傳序論説. Wenyi lilun yanjiu 2 (2013): 51-6.

- Zhu Jieren朱傑人. “Jiaodian shuoming” 校點説明.In Zhu Jieren, Yan Zuozhi, Liu Yongxiang, eds., Zhu zi quanshu 朱子全書, Vol. 1. Shanghai: Shanghai guji, 2002.