Elvin Meng, University of Chicago

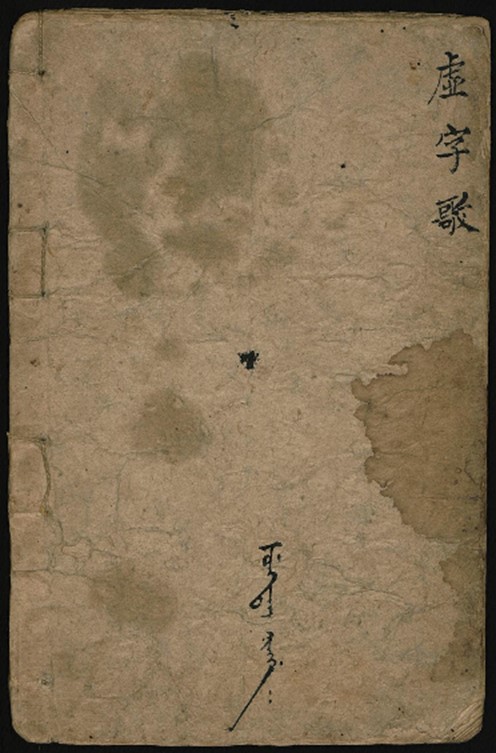

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Hs. or. 8415 (#340 in Hartmut Walravens’ 2014 catalogue), one of the many handwritten students’ workbooks in the S. A. Polevoj collection, is a multi-text manuscript of 18 stitch-bound, unpaginated folios in two hands. As with similar workbooks in the collection such as Hs. or. 8454 (Walravens #378, belonging to a Wenjy) or Hs. or. 10781 (Walravens #407, belonging to a Ioišan), on the front cover of this manuscript is a title (which in this case reads “虛字歌”) in the upper-right corner, and in the lower-middle region one finds “Žungtai ningge” followed by two ciks, “Žungtai” undoubtedly being the name of the student. The manuscript, measuring 23 x 15 cm, is undated, but the handwriting, which is in black ink, appears to be from the second half of the nineteenth century. It contains also numerous handwritten comments on grammar in a smaller hand, in black ink, as well as dots for punctuation and emphasis in red ink. There is some water damage on the front cover and the first six folios, and occasional ink stains throughout. Like many in the Polevoj collection, this manuscript is a window into “on the ground” Manchu pedagogical practices in the dynasty’s final century, which is an emergent focus of recent Manjuristic research after the earlier emphasis on court- or print-centered histories of Manchu education and literacy. The composition of the manuscript can be described as follows:

[2r]–[5v]: Preface to versified Manchu grammar. Bilingual in the hebi format, 8 lines (4 per language) per half-leaf. Incipit: Manju gisun-i narhūn ula-i bithei šutucin. Manju bithe de untuhun hergen bisirengge, uthai nikan bithe de sula gisun bisire adali 清文秘傳序。夫清文之有虛字者,猶漢文之有助語也. Explicit: kumdu gūnin amba muru be inu majige bahakū semeo, tuttu ofi šutucin araha 不稍得其梗槩也哉,是為序.

[5v]: Brief discussion of Manchu vowel harmony. 5 lines total. Incipit: kak kok tak tik tok tuk [. . .]. Explicit: 下句末後字陽尾餘者皆是陰尾.

[6r]–[16r]: Versified Manchu grammar. Mixed-language, 9 lines per half-leaf, two verses per line. Incipit: i ni ci kai 與 de ba [sic] / 用處最廣講論多. Explicit: 但只是使 damu / 而已矣用 wajiha.

[16r]–[16v]: A note on “o.” Mixed-language, 8 lines total, including the title: 附講 o 字. Full text transcribed below.

[17r]–[17v]: Fragment of versified Manchu grammar. Mixed-language, 11 lines per half-leaf, two verses per line, with ruled lines. Incipit: 寔在凡字繙 yaya / 所字往々用 ele. Explicit: ohode ebsi 怎庅好 / adarame ohode 一類説.

As the last inscribed leaf, fol. 17, is the only one with different paper and a different hand, this blogpost will focus on the first 15 inscribed leaves of the manuscript, fols. 2–16.

The versified Manchu grammar that constitutes the main text of the manuscript is clearly a variant of the “Manju gisun-i untuhun hergen-i ucun 清文虛字歌,” reproduced in full with added table of contents and extensive commentary in Heo Tiyan Wanfu 厚田萬福’s Manju gisun-i untuhun hergen-i temgetu jorin bithe 清文虛字指南編 (preface dated Nov. 18, 1884). I am aware of at least two more manuscript variants of the same verse: one is transcribed by Brian Tawney at the end of his A.M. thesis, and the other is Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Hs. or. 8398 (Walravens #326, “Untuhun hergen ucun bithe / wenlin ningge” on cover, dated Mar. 12, 1879). This list is certainly not exhaustive. Remarkably, the second variant predates the Wanfu commentary, which likewise initially circulated in manuscript form. It is interesting to note that while neither Wanfu nor Fengšan 鳳山, who was responsible for the later reprint of the Manju gisun-i untuhun hergen-i temgetu jorin bithe (preface dated 1894), specifies the source of this “ucun,” Hs. or. 8415 does contain an anonymous preface referring to the text itself as “manju gisun-i narhūn ula-i bithe 清文秘傳.” The key terms in the title, “narhūn ula,” harp upon a longstanding ambiguity in ideological enframings of the Manchu language, at once esoteric/secret and exoteric/didactically potent.

The important part of this preface, which I do not transcribe in full as the manuscript has already been digitized, is its attribution of the verse to a “friend” referred to simply as Lu Fang Sihiyan boigoji 綠芳軒主人. The rhetoric of the preface is remarkably similar to that of Wanfu’s commentary, or indeed other nineteenth-century scribal or woodblock publications of previously-private Manchu pedagogical materials. The preface begins by emphasizing the importance of “Empties” in the Manchu language (except in the later translation of “A Note on ‘O,'” I use literal translations of Manchu grammatical terminology), and then proceeds to cite this friend’s opinion that the market is now flooded by Manchu grammatical treatises that are at times too complicated, too difficult to understand. The two of them thus composed this song (ucun or 歌) by referencing both the imperial Mirror and previous treatises, specifically with the aim that it should be taught to students, who were to read it until it is more-or-less internalized. The preface then references a formula for the Manchu eight-legged essay which the authors taught the students when they have thoroughly studied this verse, but this formula is not included in the manuscript. The preface continues by describing the popularity of this set of pedagogical texts of which the song is a part, and that the friend was prompted to share it with the world by print publication. The preface was apparently written for the occasion of this print publication, although I know of no extant imprints with the title Manju gisun-i narhūn ula-i bithe 清文秘傳. It concludes by stating two benefits of learning Manchu: to acquire real knowledge (yargiyan tacire de tusa niyececen obuci ojoro 裨益寔學) and to aid in examination (gungge gebu be gaijaci ojoro 义取科名).

The “song” itself is interesting for a variety of reasons, and a study of its transmission using the aforementioned textual witnesses still awaits the interested scholar. But the basic grammatical terminology it uses, which is also attested in other sources for day-to-day Manchu language pedagogy, is more or less the same as those proposed by Shen Qiliang 沈啟亮 (fl. 1645–1693) in the third part of his Manju bithei jy nan 清書指南 (preface dated 1682), albeit in a much more scholastic mode. (I am unable to determine if Shen Qiliang was influenced by earlier grammatical traditions, or this vocabulary was developed completely ex novo. For a study of this terminology, see Takekoshi’s helpful article.) One thus finds there the basic categorization of Manchu lexemes into the Full (gulhun gisun 整字, roughly nouns and adjectives), the Dispersed (faksalaha gisun 破字, verbs), and the Empty (untuhun gisun 虛字, affixes), and instructions on telling them apart. Aspect and voice are discussed as matters of already-so (已然) or not-yet-so (未然) on the one hand and the presence or absence of force (力) on the other. Other helpful advice can be found throughout on how to modify a Chinese text with Manchu word order, and the proper correspondence between Chinese and Manchu idioms.

But for the most part, both the song and Shen Qiliang’s original treatise focus on affixes and their relation with auxiliary verbs, which leaves little room for the discussion of the verbal root as such. This is why the short text appended to the end of the song, simply titled “附講 o 字” (appended discussion on the letter “o”), is particularly notable, as it does not always accompany the “Untuhun hergen-i ucun.” The text is transcribed as follows, with my punctuation reflecting the added dots in red ink in the original manuscript.

Ombi 以實字講係可字,以虛字講則係聯上接下之字。蓋清文之 mbi 字,如遇 ra re ro 並 ha he ho fi me 字等之處既無 mbi 字可接,亦無硬連之理,故遇有 ra re ro 則無 ojoro 與 ha he ho 則用 oho, 與 me 字則用 ume, 遇 fi 字則用 ofi 推而之如遇 mbi 則用 ombi, 如遇使令此則用 oso, 凡不能聯不能轉者皆以用 o 字,代之則 o 字乃聯上轉下之詞也。

Before attempting a translation, I should note that the original text, diplomatically transcribed here, is quite idiosyncratic. For example, the phrase “故遇有 ra re ro 則無 ojoro” is clearly parallel to the remaining phrases where the different form “o” takes upon encountering different affixes is enumerated, and thus “無” cannot be anything other than its logical opposite, “用.” “Ume” seems to me an obvious corruption of “ome.” “遇” is written phonetically twice (and only twice) with “與” for no apparent reason, and “推而之如[. . .]” could have been any number of more coherent formulations such as “推而知如[. . .]” or simply “推之而[. . .].” Finally, the penultimate punctuation between “字” and “代” I give here follows solely from the annotation in the original manuscript, and it is entirely possible to create a new meaning by moving the break two graphs later, to between “之” and “則.”

From elsewhere in the Polevoj collection, we know these workbooks to have been copied by teenage students themselves, and thus the appearance of these errors (along with the still-immature Chinese handwriting) are understandable (see, e.g., Hs. or. 10781 and Hs. or. 10791, both incorporating the personal information of the student, who were 16 and 13 se respectively, into its dialogues). It should also be noted that students often copied such texts without fully understanding them, and only intensively and slowly studied their content after the manuscript workbook is completed. Now, with these issues out of the way, I can attempt a somewhat liberal translation.

Taken as a main verb, “ombi” means “to be permissible.” Taken as a helping verb, it is something that connects what comes before with what comes after. Now, take the affix “mbi” in the Qing language. When you find the affixes “ra,” “re,” ro,” “ha,” “he,” “ho,” “fi,” or “me” already in place, you cannot further forcibly affix “mbi” to the lexeme. So when “o” encounters the “ra,” “re,” “ro” group of affixes one uses “ojoro,” when it encounters the “ha,” “he,” “ho,” group one uses “oho,” when it encounters “me,” one uses “ome,” and when it encounters “fi,” one uses “ofi.” Extrapolating from this, we know that when “o” encounters the “mbi” suffix, one uses “ombi,” and when encountering words of command one uses “oso.” “O” can be applied whenever words cannot be connected or conjugated. Thus, “o” is the word that connects what comes before with what comes after.

The conceptual movement of the text is admittedly still somewhat opaque, but it is at least no longer incoherent. The subject of the short essay is clearly “ombi,” and some attempt is made to explain what happens to the word “o”—here the group of conjugated forms is clearly referred to as a collective by its unchanging part—when different affixes needed to be applied to it. We should keep in mind that this somewhat awkward way of talking about verbal conjugation is a result of the affix-centric system of describing Manchu grammar, within which the entity that retains a degree of individuation despite its incorporation of a variety of affixes can be surprisingly difficult to endonymically describe.

Finally, the somewhat cryptic ending of the text can perhaps be partially elucidated by the “Manju gisun-i untuhun hergen-i ucun” itself, especially the discussion on how “ombi” can help transform a Full into a Dispersed. I conclude this post by quoting the relevant verses and its commentary.

ombi 若要接整字 / 不作可以作為說 / 整字難破接 ombi / 猶如 lambi 作法活。

If you append “ombi” to a Full, don’t use it as “permissible,” but translate it as “to be.” If a Full is difficult to disperse, append “ombi” to it, and like “-lambi” it is quite flexible ([9r]).

Commenting on this line, Wanfu’s aforementioned commentary gives an example from the 1755 Qianlong translation of the Duin bithe, specifically from Mencius 7.2 (Mengzi xia: 3v in the linked edition):

ejen ofi ejen-i doro be akūmbuki, amban ofi amban-i doro akūmbuki seci [. . .]

欲為君盡君道,欲為臣盡臣道 [. . .]

One Reply to “Note on a Note on “O” in Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Hs. or. 8415”