Editor’s note: This guest blog post is written by Tim Brookes, executive director of the Endangered Alphabets Project, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization based in Vermont, U.S.A. Among the organization’s many achievements in its mission to “preserve and revitalize endangered cultures by researching, cataloging, and promoting their indigenous writing systems” are exhibitions and talks at universities and libraries, an online encyclopedia, and conversations with scholars around the world on indigenous writing systems.

While the Manchu Studies Group blog has traditionally been a platform for Manjurists to share their writings with each other (and this will remain its primary function), historically speaking, an important aspect of Manjuristic research has always been its attention toward, dialogue with, and import for broader communities of people who engage with the Manchu language, script, history, and culture in the contemporary world. It was to continue this spirit that I have invited Tim Brookes to contribute a short note describing the role of Manchu in the Endangered Alphabets Project, as well as any message the organization might have for the Manchu Studies community. This post will hopefully mark the beginning of new kinds of conversations, both on this blog and beyond.

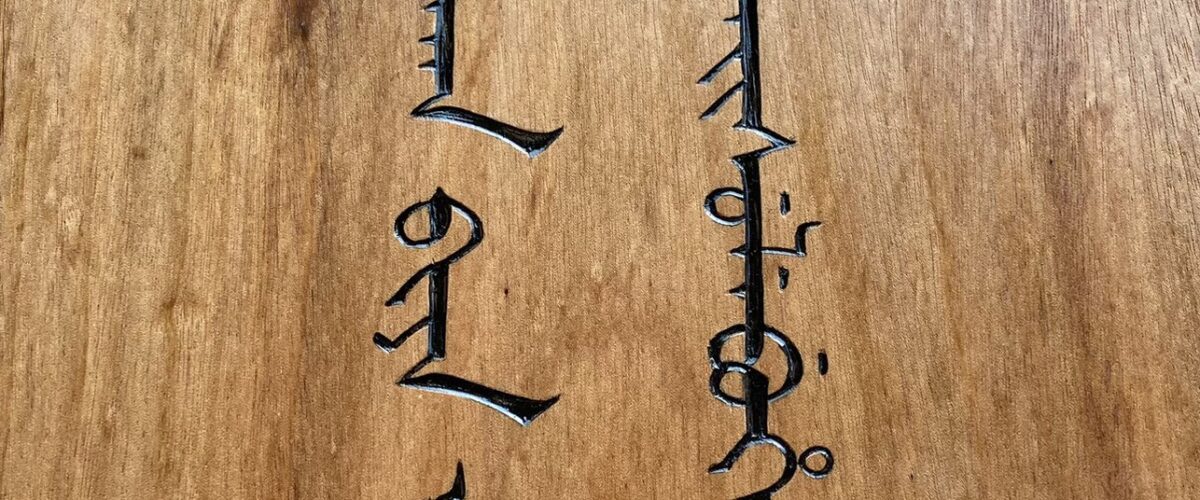

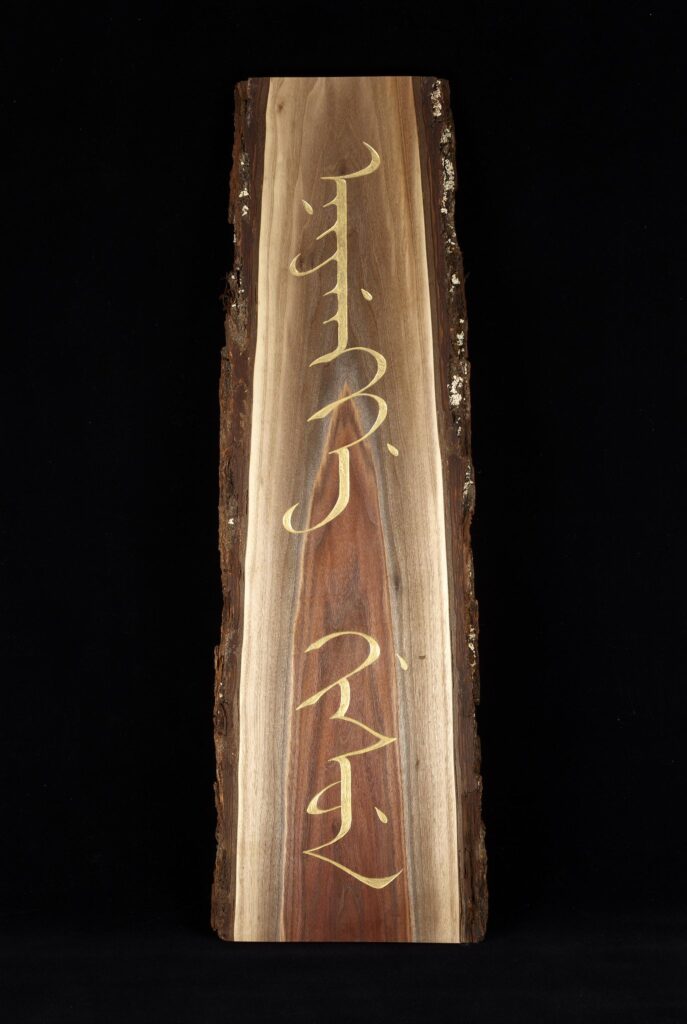

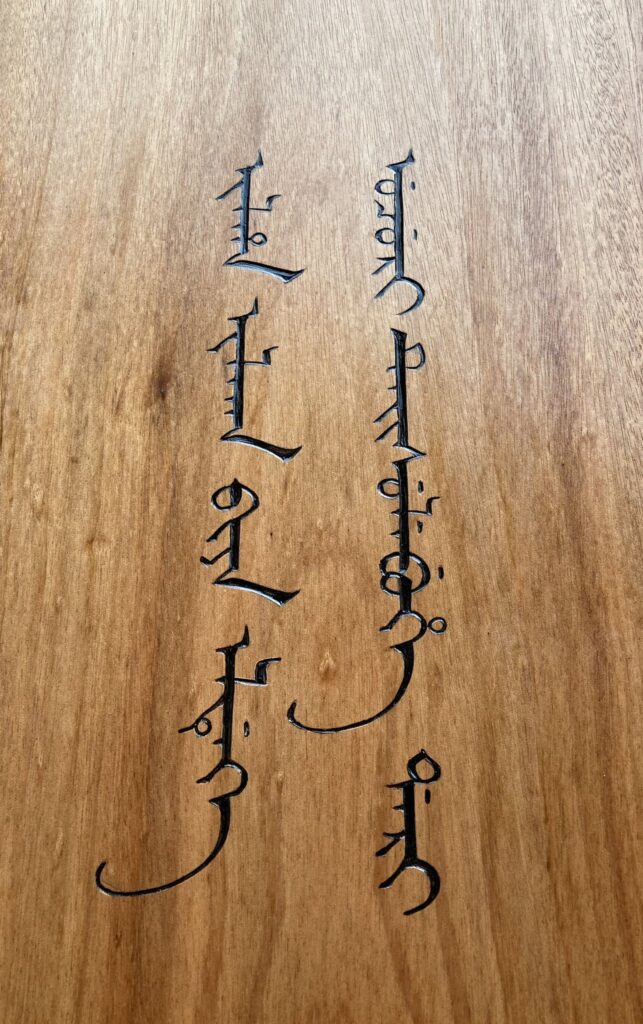

When I began to research and carve indigenous and minority writing systems, 14 years ago, I was fascinated by Manchu. I had never seen a vertical script before apart from on battle flags in Kurosawa movies, and in fact I knew almost nothing about the full range and diversity of the world’s writing systems. I also knew very few scripts that automatically connected the letters that formed a word, or had the delightful initial and final flourishes that are characteristic of the Manchu and Mongolian scripts.

In addition, my only source of information at the time was omniglot.com, whose text informed me that perhaps only a dozen native users of the script still lived. It must therefore be one of the most endangered scripts in the world.

Unfortunately, this meant it was also one of the hardest to find, or to find out about. At the time, Omniglot gave a grid of Manchu letters but no piece of text to carve—especially not Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was the subject-text for my first exhibition of carvings. Searching the web, I finally came upon what claimed to be a site that translated English into Manchu. I typed in the English version of Article One, and out came the classic beaded curtain of Manchu letters, which I duly carved—and, so impressed was I with the result, I photographed the finished carving and made it the background of the Endangered Alphabets’ first business cards.

It was not until some time later that I realized I had made a ghastly mistake. The site I had used did not translate—it merely transliterated the sounds into Manchu letters. The carving of which I was so proud was, in fact, bogus.

More than a dozen years later, my range of carvings has vastly expanded, my knowledge of the world’s minority and indigenous scripts is perhaps greater than anyone else’s, but I am still very poor in Manchu contacts. Over those 12+ years I did only one carving in Manchu; I am almost finished with another. I’ve also done a fair amount of research. But I would dearly love to hear from many Manjurists—about their own knowledge and use of the script, about their understanding of its history and the ways and degree to which it is used today, about its changes of revival.

In fact, I am strongly considering doing a special report on Manchu for the World Endangered Writing Day (WEWD) website. WEWD will consist of a daylong series of talks and discussions about scripts and script revival, but I’ll also have reports and videos on the website (endangeredwriting.world, due to go live in about a week). I have been sent photos and a news article by a Manchu calligrapher—what else can you send me? Stories? Pictures? Photos? Video? All these will help toward my goal for WEWD, which is to draw attention to the world’s threatened scripts and the efforts being made to revive them. Please send me anything you like to [email protected], and I will combine everything I receive into something for the world to read and marvel at.

Thanks!

Tim

Images: Tim Brookes, “Eniyengge gisun” and “A Phrase by Jakdan.” Carvings on wood. Photos courtesy of Tim Brookes, the Endangered Alphabets Project.

For more information on the Endangered Alphabets Project, see www.endageredalphabets.com and the Atlas of Endangered Alphabets at endangeredalphabets.net.