By Elvin Meng, the University of Chicago

In January 2025, through a Friends of the Princeton University Library Grant, I had spent around three weeks at Princeton University examining its collection of Manchu and Mongolian rare books and manuscripts. In this process, I had benefitted immensely from the hospitality, expertise, and encouragement of Martin Heijdra, who both in conversation and through publications (such as his 2020 article) helped me understand the history and scope of this rather impressive collection. These Manchu and Mongolian titles are not yet in the library’s online catalog, but scans of the older card catalog generously provided by a colleague allowed me to manually request the items in the Special Collections. The length of my stay allowed me to view the Manchu-Mongol rare book collection in full and collect bibliographical details of the roughly one hundred titles in a spreadsheet. Before these titles appear in the library’s online catalog (which, I have been told, will happen in the next year or so), I am happy to share this spreadsheet, as well as my photographs of the items, upon request with any colleague in Manchu studies.

With the encouragement of Martin Heijdra and Bian He, I am writing this two-part note to introduce a few significant items from this collection. Some of these items have already been noted in Kanda Nobuo’s survey of Manchu rare books in Euro-American collections (pp. 77–78). I will describe the manuscripts first, followed by printed books, grouping similar items together rather than following the order of their call numbers. It goes without saying that my discussions below are highly cursory ones of items that await much more diligent and specialized analysis.

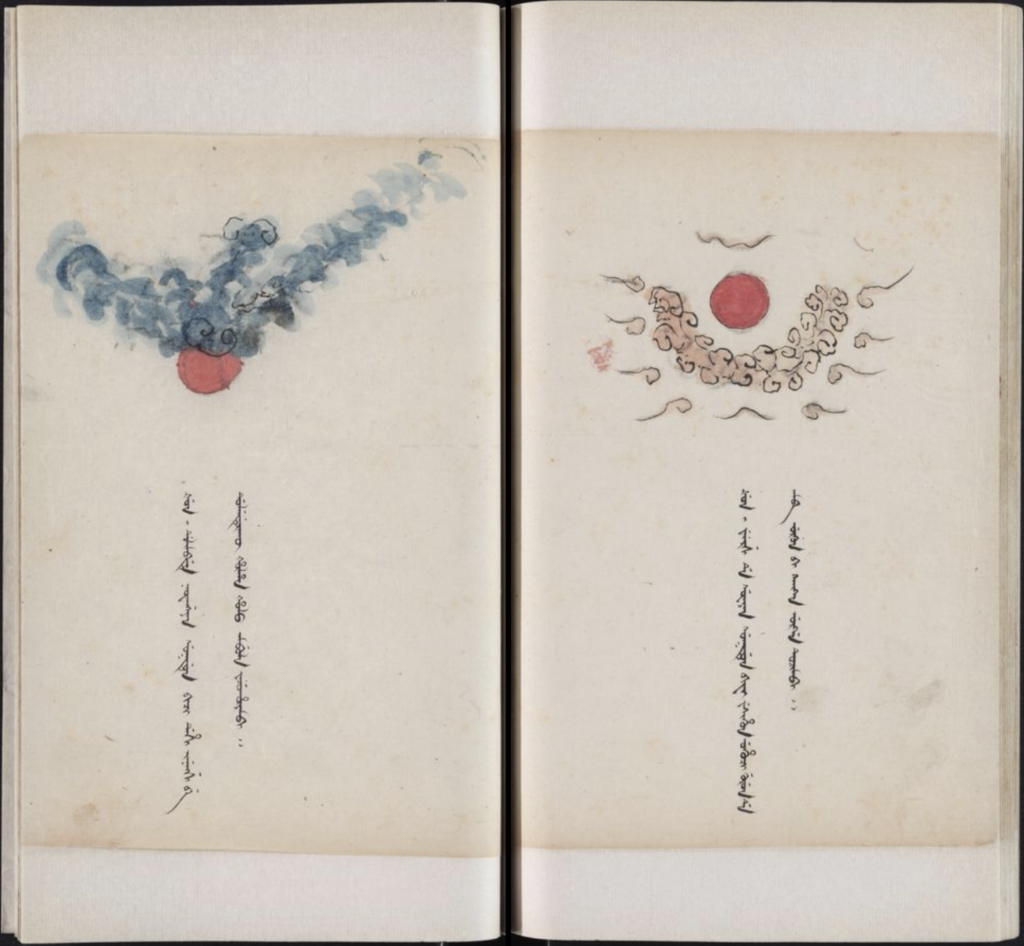

The most eye-catching item in the collection is probably the unique four-volume color-illustrated manuscript with call number TB157/3922, with the title 滿文日月星辰占 written on the case in which it is stored. The manuscript is fully digitized, and is the subject of a 2015 article by Hartmut Walravens. It is a divination manual in elegant Manchu calligraphy, with beautiful multicolored illustrations in the top half of most pages. There are no volume or page numbers within the manuscript itself, except for Chinese numerals written on the feet of the codices labeling them as vols. 1–4. These numbers are suspicious, as the “second” volume opens with a more theoretical overview of Neoconfucian cosmogeny and the basic principles of meteorology (ff. 1–9), followed by a page reading “ereci amasi šun-i hacin” and subsequent illustrated descriptions of various solar phenomena and their interpretations. As all other volumes only contain lists of solar phenomena and their interpretation, it is possible that vol. 2 is in fact the opening volume of a larger set that is only partially extant, as there is neither depiction nor analysis of any phenomena related to the moon and the stars. (Image: 1:3v–4r of TB157/3922 滿文日月星辰占. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

The significance of celestial phenomena given in the manuscript, notably, tends to be related to military campaigns and the welfare of the empire, a fact that might be useful in determining the context in which this text was originally produced and read. (It stands in contrast, for example, with a divinatory manuscript at the University of Chicago, whose readings are related to official careers, weather, household matters, and suchlike.) On four occasions, in the upper-left corner of a page depicting a certain celestial phenomenon, exact dates are given to record its actual occurrence: on vol. 1:1v (“dehi sunjaci aniya ilan biyai ice nadan de ere adali bihe”), vol. 2:18v (“dergi sunjaci aniya duin biyai ice de suwayan singgeri inenggi coko erinci jefi šun tuhetele dulin sabuhakū”), vol. 3:17v (“dehi sunjaci aniya juwe biyai ice juwe de ere adali bihe”), and vol. 4:16v (“yong jeng-ni jai aniya juwe biyai ice nadan de šun-i boco biyai adali bihe ice ninggun de amba edun dahambihe”). The unusual reference to the Yongzheng reign as “yong jeng” rather than “hūwaliyasun tob” notwithstanding, these dates allow us to date the manuscript to sometime after Qianlong 45, and probably before the end of the Qianlong reign in 1796 (since otherwise his reign name would not have remained implicit).

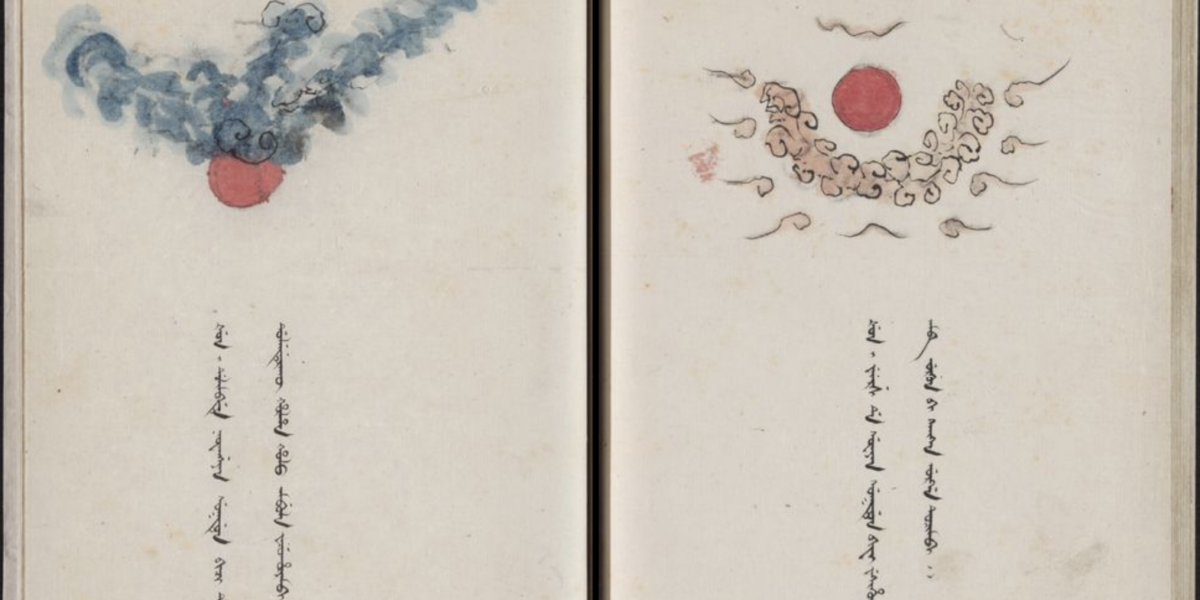

Another notable manuscript of a religious nature is Han-i araha akdun yabungga nomun | 御譯首楞嚴經 in 10 volumes, call number TC513/4015. It is a Manchu-Chinese bilingual copy of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra (Manchu Canon No. 162, T. 945), translated into Manchu from Chinese on the order of the Qianlong emperor in discussion with the 3rd Changkya, Rolpa’i Dorje (1717–1786). The elaborate preface summarizes the transmission history of Buddhadharma from India to Tibet and China and discusses the absence of sutras such as the Śūraṅgama Sūtra in the Tibetan canon (which is attributed to the destruction of Tibetan Buddhism under Langdarma, r. 841–842). The Manchu translation itself—supervised by Tob cin wang 莊親王, undertaken by the 3rd Changkya and Funai 傅鼐 (1758–1811), and proofread by the emperor himself—began in 1752 and concluded in 1763, when the Qianlong emperor penned his preface (dated QL28.10.18). According to his preface, it was to serve as the basis for further translations into Mongolian and Tibetan.

The library’s copy is thread-bound, rather than in the pecha format of the Manchu Buddhist Canon. As such, it is (to my knowledge) the only one of its kind. The emperor’s postscript is followed by the triple refuge in Sanskrit (written with Manchu letters) and Chinese: na mo bu ddha ya 皈依佛 / da mo dha rma ya 皈依法 / na mo sa ṅgha ya 皈依僧. This is followed, in the Tibetan fashion, by titles of the sutra in Sanskrit (labeled “梵語,” in Manchu letters), Tibetan (labeled “堂古特語,” in Manchu letters), Manchu (labeled “華言”), and Chinese (in characters). The main text is in the interlinear format, in Manchu and Chinese. A red seal on the first leaf reads “?堂齋” (first character has 工 above and sideways 車 below). The red seal on the last leaf reads 暫為我有. (Image: 1:5r of TC513/4015 Han-i araha akdun yabungga nomun | 御譯首楞嚴經. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

The collection also contains four sets of very fine, large format manuscript codices, in print-style calligraphy (a style known in Manchu as gingguleme arambi), in black ink with red frames. They appear to be internal drafts of various high-level imperial institutions, dating from the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries.

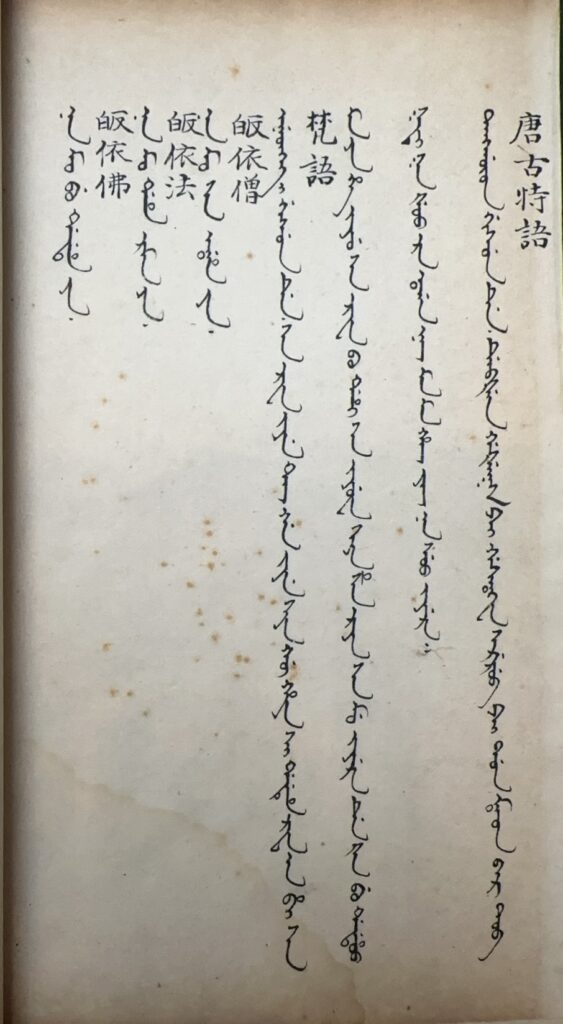

The first of these manuscripts is a draft genealogy of the royal lineage in Manchu, call number TB107/4005, in one volume and without pagination. The pasted-on title-slip reads Daicing gurun-i ijishūn dasan hūwangdi han-i uksun-i ejehe-i jise | 大清順治皇帝玉牒草稿, but this title is possibly added later, on account of the fact that this volume begins with the sixth generation of the royal lineage, headed by the Šidzu eldemungge hūwangdi. A more accurate title would simply be Daicing gurun-i han-i uksun-i ejehe—the genealogy of the royal lineage of the Qing empire, a document that was compiled every nine years by the Court of the Imperial Clan or Zongrenfu 宗人府, of which this is an incomplete draft. Incomplete, as it begins with the sixth generation and ends in the middle of the ninth. It is possible—based on internal evidence—to determine that this is a draft of the Kangxi 45 (1706) compilation of the genealogy, the finalized version of which is now held in the Third Historical Archives in Mukden. (Image: 1r of TB107/4005 Daicing gurun-i ijishūn dasan hūwangdi han-i uksun-i ejehe-i jise | 大清順治皇帝玉牒草稿. Annotations and handwriting on laid-in index card likely by an earlier librarian. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

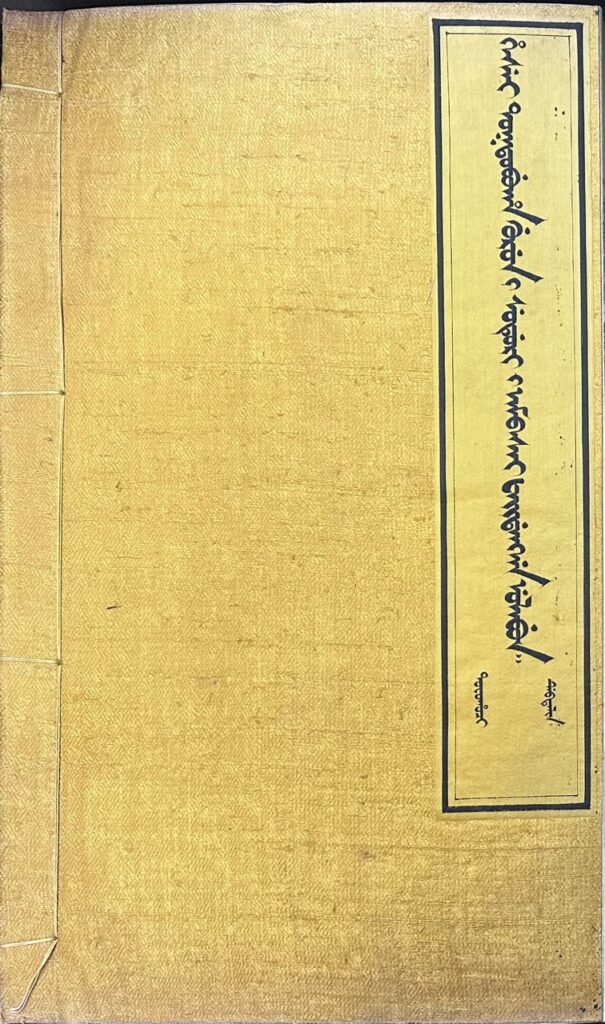

The second of these manuscript is a set titled Hesei toktobuha gurun-i suduri-i ambasai faidangga ulabun | 欽定國史大臣列傳, call number TB157/3832, in 24 volumes and housed in 12 cases. Written entirely in Manchu, the work contains biographies of Qing officials, mostly of the Manchu and Mongol Eight Banners, who were active from early to mid-nineteenth century. The Manchu title is taken from the (likely original) yellow title-slip on the covers, which are made of yellow brocade. Each volume opens with a list of the names of officials whose biographies are included, and these names are transliterated into Chinese—likely by a librarian—on a piece of paper pasted onto the first leaf of each volume. These pasted-on pieces of paper also give the Chinese title of the work, as well as the case and volume number. They are likely added later for two reasons: one, they sometimes fail to include the names of officials written on the verso of the first leaf; and two, the case and volume numbers reflect the current, incorrect housing of the volumes in cases.

The first volume and the preface (if there is one) being absent, it is difficult to determine the exact date and circumstances around this work’s compilation. Being materials in preparation for a future dynastic history, documents by this title were compiled many times throughout the Qing, five sets of which (of various numbers of volumes) are still present in the Palace Museum dating to as late as Guangxu 6 or 1880 (see 北京地區滿文圖書總目, 0769–0773). A comparison of names suggests that many of these biographies did not enter the Qingshigao 清史稿 compiled in the Republican period. These names also appear to be absent in Chinese language drafts of the biographies of Qing officials, which predominantly feature Han Chinese officials. Given the potential value of these otherwise difficult-to-access Manchu language biographies, I have appended a comprehensive transcription of the list of names, organized by volume, to this blogpost, for those who wish to consult this manuscript. Note that the set is incomplete. (Images: Cover and 1r of vol. 15 of TB157/3832 Hesei toktobuha gurun-i suduri-i ambasai faidangga ulabun | 欽定國史大臣列傳. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

The third of these draft manuscripts is a set titled Dorolon-i jurgan-i kooli hacin-i bithe | 禮部則例, call number TB282/2397b. It is a Manchu monolingual draft of the Code of the Board of Rites whose content totals to 186 debtelin according to the list of contents (hence 187 debtelin in total). Of these, 65 debtelin are extant, bound as 23 volumes and housed in 4 cases. The total number of debtelin differs from two common juan counts of Chinese language versions of the Code, which are 194 juan (e.g. the Qianlong 49 or 1784 and the Qianlong 60 or 1795 versions) and 202 juan (e.g. the Jiaqing 25 or 1820 and the Daoguang 24 or 1844 versions). In addition to the list of contents, there are debtelin 1–10 (5 vols, in ujui dobton), debtelin 45–47, 56–58, 114–122, 127–130 (6 vols, in duici dobton), debtelin 43–44, 48–55, 123–126 (5 vols, in ningguci dobton), and debtelin 81–101 (6 vols, in jakūci dobton). There is no date or list of compilers in this manuscript.

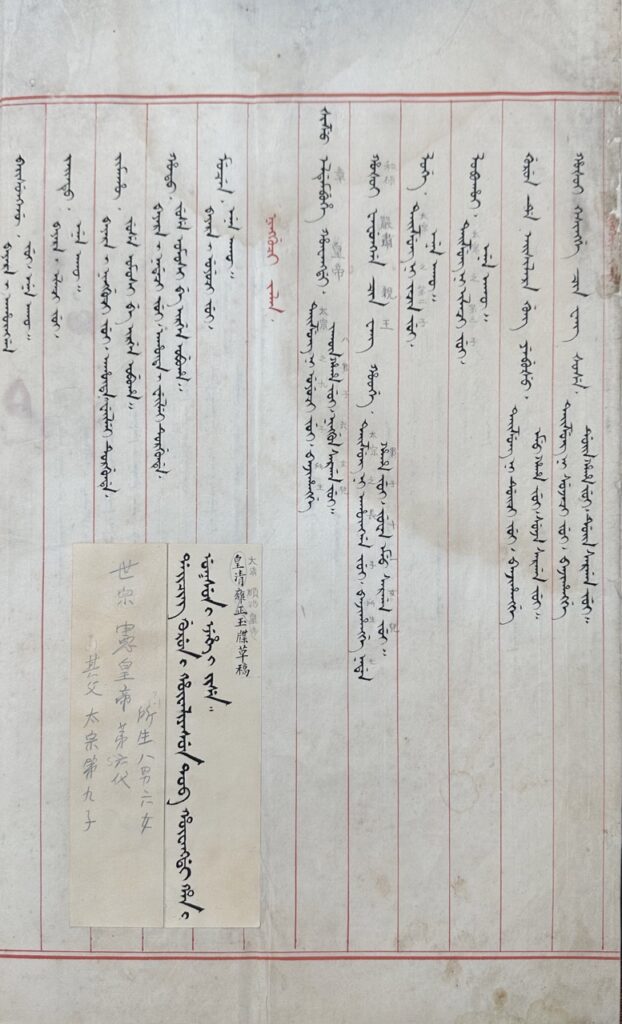

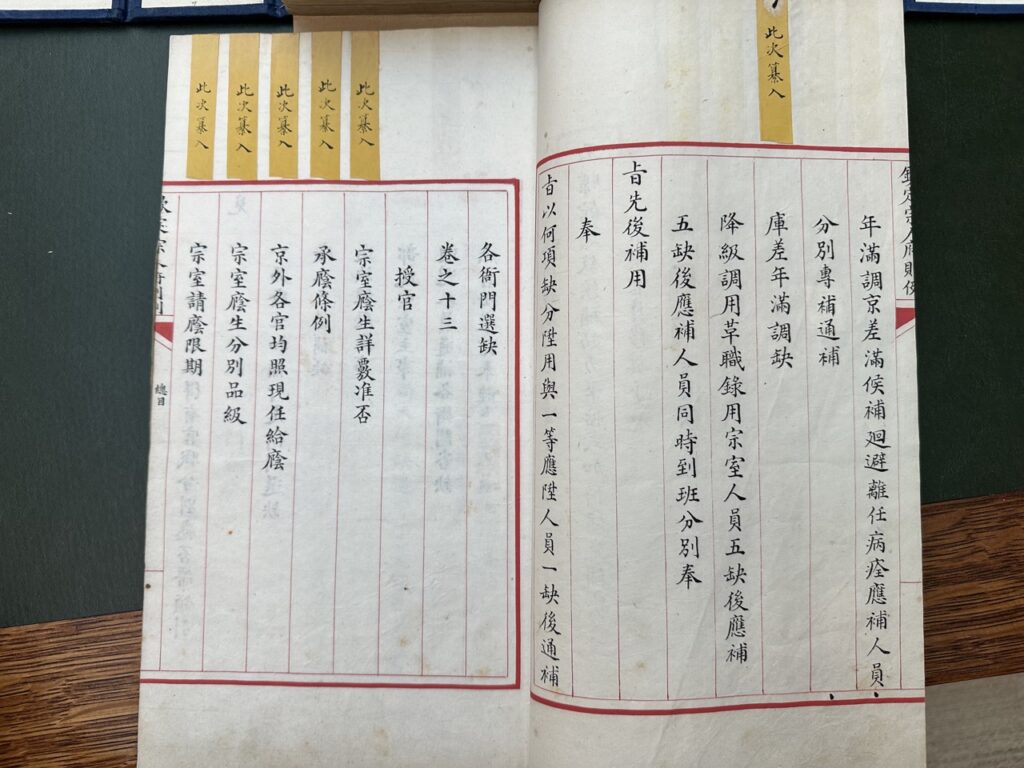

Finally, there is the curious case of 欽定宗人府則例, call number TB282/2397a, a work entirely in Chinese but somehow has been grouped together with the Manchu and Mongolian volumes. It is a draft of the Code of the Court of the Imperial Clan, in 32 juan (1 list of contents and 31 numbered juan), bound as 32 volumes and housed in 4 cases. The petition to revise the Code is dated to Guangxu 4 or 1878, and the list of officials involved in its revision is listed at the end of the first, list of contents volume, beginning with the five supervising princes. The draft contains numerous handwritten additions and corrections in black ink, and in the first, list of contents volume, all sections that have been added to or altered from the previous version have been marked by a pasted-in yellow paper-slip in the top margin bearing language such as “此次纂入” or “此次奏改.” (Image: Pasted-in paper-slips in the list of contents volume of TB282/2397a 欽定宗人府則例. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

Appendix I: List of biographies in TB157/3832 Hesei toktobuha gurun-i suduri-i ambasai faidangga ulabun | 欽定國史大臣列傳

Sinographic transliterations of personal names taken from the pasted-in paper-slip, and will not always correspond to standard renderings of the names in, say, the Qingshigao 清史稿. The set is incomplete, and the volume numbers below correspond to the debtelin numbers on the title-slips.

Vol. 7: Sekjingge 色克經額, Ujungge 烏忠額, Uksun Agui 宗室們等, Uksun Cenggeng 宗室成綱, Boocang 寶常.

Vol. 8: Gioro Hailing 覺羅海齡, Ingsui 應水, Boošan 寶山, Arbangga 阿尔邦阿.

Vol. 9: Binliyang 彬良, Huihiyan 輝先, Pujy 溥志, Guwanšengboo 關聖寶.

Vol. 10: Hafungga 哈豐阿, Guiling 桂齡, Siokun 秀坤.

Vol. 11: Uksun Gungpu 宗室公普, Uksun Deceng 宗室德程, Uksun Minghingga 宗室明星阿, Uksun Huiduwan 宗室惠端.

Vol. 12: Sunghui 松惠, Uksun I Je 宗室伊蜇, Cengduwan 承端, Bodisu 伯第蘇, Linggiyan 靈減, Guide 貴德.

Vol. 15: Ioikiyan 玉虔, Linking 林慶.

Vol. 16: Funiyangga 福尼揚阿, Huigi 惠老.

Vol. 17: Sebsingge 色普興額, Urgungge 烏尔公額.

Vol. 18: Cangcing 常慶, Bahabu 巴哈布.

Vol. 23: Lešan 樂山, Sungpu 松普, Uksun Gingmu 宗室景木.

Vol. 24: Nayamboo 那延寶, Žunggan (deo Žungjao kamciha) 榮干 (弟榮昭兼製).

Vol. 25: Uksun Tiyelin 宗室鐵林, Liyanging 連經.

Vol. 26: K’aiyembu 凱葉木布, Uksun Siyangkang 宗室祥康, Guncuktsereng 棍出克策楞.

Vol. 27: Anaboo 阿那寶, Anfu 安福, Harangga 哈郎阿.

Vol. 28: Yande 延德, Gungcukcab 公出克扎布, Sucengge 蘇呈額.

Vol. 29: Šutungga 舒童阿, Giltungga 吉樂童阿, Werentai 臥樂恩太, Ciowanlingga 全齡阿, Ortoyan 臥尔端, Hailing 海齡.

Vol. 30: Elgiyengge 額尔經額, Hinglun 興倫, Canghi 常喜, Mergene 莫尔閣那額, Jatamboo 扎塔莫寶, Šuwengge 書文閣, Dasan.

Vol. 33: Sanceng 三程, Susultungga 蘇蘇勒同阿, Cangde 昌德, Salungga 薩隆阿, Guwanfu 官福, Cangheng 常恆, Sirangga.

Vol. 34: Alungga 阿隆阿, Ingšeo 應壽, Šan’ing 山英.

Vol. 45: Alingga 阿齡阿, Hūwašana 花沙那.

Vol. 46: Uksun Hian (ini deo Ioi’an kamcibuha) 宗室熙恩 (其弟玉恩兼製).

Vol. 47: Alcingga 阿尔清阿, Tedengge 特登額.

Vol. 48: Dehing 德興, Huifeng 惠豐.

One Reply to “Highlights of Manchu and Mongolian Rare Books and Manuscripts at Princeton, Part I: Manuscripts”