By Elvin Meng, the University of Chicago

Generally speaking, it is far more likely for a manuscript to be one-of-a-kind than it is for a printed book, which by definition tends to be produced in larger batches of nearly identical copies. I will highlight below five printed items that are unusual in one way or another. One of them is, to the best of my knowledge, indeed the sole extant copy of an edition that is furthermore an interesting source for Sino-Manchu literary history. All four remaining items are Mongolian books, two of which notable for their handwritten annotations by their authors while the other two being early examples of movable type Mongolian (or todo bičig) printing.

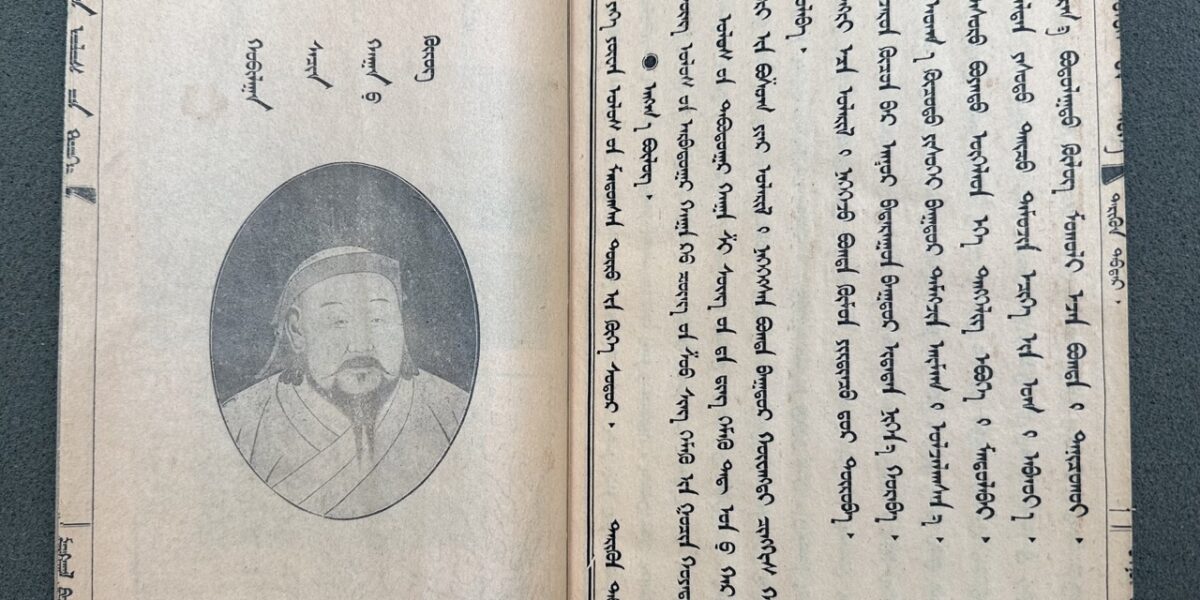

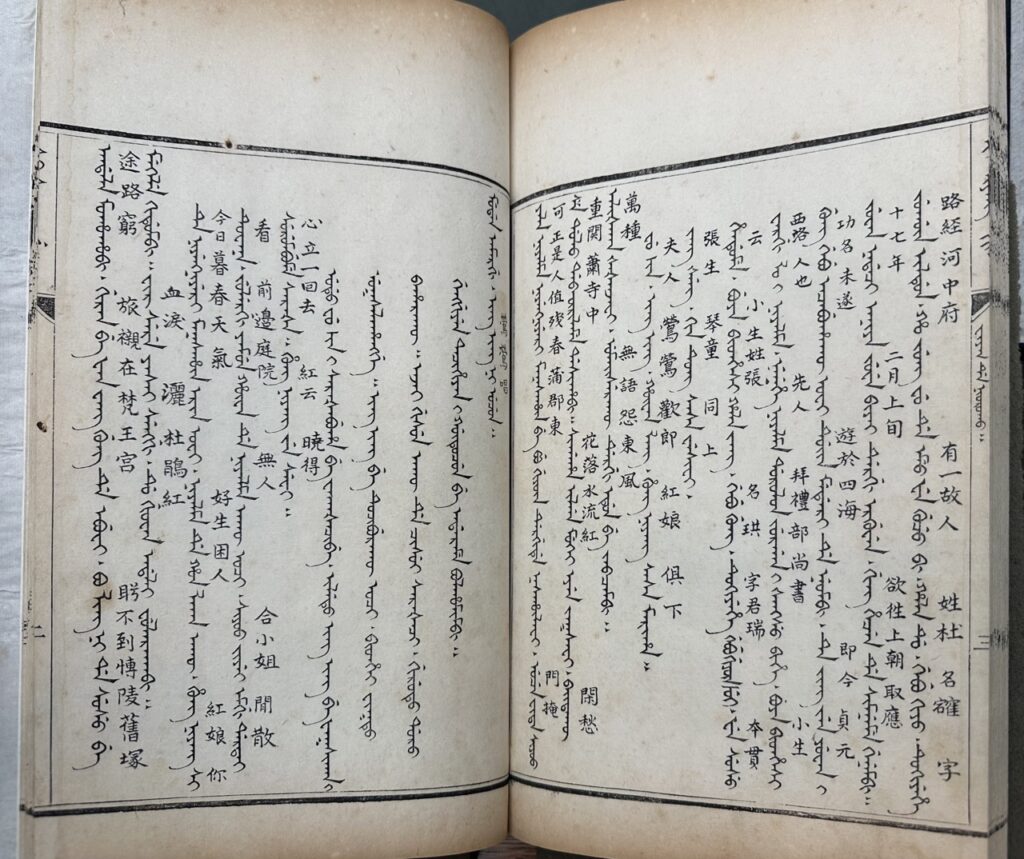

Ubaliyambuha si siyang gi bithe, call number TD143/1881, is a very unusual copy of the Xixiangji 西廂記 in Manchu. It is the twelve-scene version of Jin Shengtan 金聖嘆 (1610–1661), printed in Manchu in four debtelin, housed in one case. In addition to the text of the play, the edition includes a “sioi” in 5 half-leaves and a “si siyang gi-i leolen” in 4 half-leaves. These are followed by the main text, which begins with a table of contents. From this table of contents onwards, the Manchu text is accompanied by the Chinese original, added by hand in black ink in the interlinear hebi format. (The handwriting of the Chinese is so fine that I thought at first that it had been printed.) The text of the play and its lyrics are sometimes interrupted by short commentaries that are indented on the page, for which no Chinese text has been added (similar to the preface and the “leolen”). There are minor handwritten corrections to the Manchu and Chinese texts throughout. (Image: 1:sioi 2v–3r of TD143/1881 Ubaliyambuha si siyang gi bithe. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

In the aforementioned article, Kanda Nobuo has already pointed out that the Manchu text of this copy differs from the much more common, Kangxi 49 (1710) bilingual edition of the play, as well as a Manchu monolingual xylographic copy in the British Library. While neither the preface nor the “leolen” are dated, there are hints at the identity of the translator: two printed seals at the end of the preface read (according to Kanda) “sanding hakcin” and “ubaliyambure araha.” The reading of the first seal is difficult, since the first letter differs in shape from the typical seal script “s,” but I fail to propose a better reading. At the beginning of the table of contents, there is furthermore the title “Ging ši jai-i ubaliyambuha si siyang gi bithei uheri fiyelen ton,” and the first three syllables are glossed in manuscript as “竟是齋.” Whether or not these sinographs are correct, it is likely that “sanding hakcin” and “ging ši jai” are the names of the translator. (Image: 1:2v–3r of TD143/1881 Ubaliyambuha si siyang gi bithe. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

What is clearer than the identity of the translator is the source of the “leolen” and running commentaries in the book, which are without Chinese translations. They are clearly paraphrases of Jin Shengtan’s (much more elaborate) “dufa 讀法” and running commentaries in his edition of the play, the Sixth Book of Genius (diliu caizishu 第六才子書). Consider the first item from the “leolen,” compared with the first item of Jin Shengtan’s “dufa” (in the interest of accessibility, I quote from the 1884 bicolor xylograph digitized on HathiTrust).

ememu hendurengge . si siyang gi serengge . dufe bithe kai sembi .. ambula acahakūbi .. ere bithe ja akū kai . abka nai ferguwecuke šu .. abka na biheci . siden de ini cisui ere ferguwecuke šu tucinjihebi .. waka oci . we erebe mutembi .. (1:leolen 2v)

Some say that Xixiangji is an indecent book. This is greatly erroneous. This book is not at all simple. It is the wondrous book of heaven and earth. From when there were heaven and earth, between them this wondrous book came forth naturally. If not, who could have written it?

有人來說《西廂記》是淫書,此人日後必墮拔舌地獄。何也?《西廂記》不同小可,乃是天地妙文。自從有此天地,他中間便定然有此妙文。不是何人做得出來,是他天地直會自己劈空結撰而出。若定要說是一個人做出來,聖歎便說,此一個人即是天地現身。(2:1r–v)

Some say that Xixiangji is an indecent book. That person must someday fall into the Hell of Tongue-Ripping. Why? Xixiangji is no simple book—it is the wondrous book of heaven and earth. From when there were heaven and earth, between them there is destined to be this wondrous book. It is not something that someone can compose, but instead it forms itself directly in the space between heaven and earth. If one must say that it is someone’s composition, Shengtan will say that this person must be a manifestation of heaven and earth.

Compare, also, the first commentarial entry in the first scene, after Hung Niyang says “je” (in the Chinese, 紅云曉得), across the Manchu and the Chinese texts:

udu fu žin-i sarašabuha be wakašacibe . iletu ing ing be faksikan-i baharakū .. ajai gisun akū de cisui sarašaci . girutu doro genggiyen tacihiyan-i gūtucun be adarame bolhomimbi .. (1:2v)

Although [the author] criticizes the old woman for leading them on an excursion, it obviously is cleverly keeping Ing Ing from getting implicated. If she wanders out on her own without her mother’s permission, how would she clean herself of the defilement of the way of chastity and the teachings of propriety?

[…] 雖曰罪老夫人之辭,然其實作者乃是巧護雙文。蓋雙文不到前庭,卽何故爲遊客悞見?然雙文到前庭,而非奉慈母暫假,自何以解於女子不出閨門之明訓乎?[…] (4:12v)

Although these are words criticizing the old woman, it is in fact the author cleverly protecting Ing Ing. If she does not come to the front garden, how would she be stumbled upon by a visitor? But if she comes to the front garden without relying on her mother, how would she explain herself regarding the clear teaching that a woman should not exit her chamber door?

The relation between Jin Shengtan’s commentary and the Manchu commentary should be clear, even if the exact patterns of this translingual paraphrasing awaits further study, especially in the broader context of the Xixiangji’s Manchu reception. However, I have not been able to find the “original”—if there is one—of the preface to this Manchu edition; it is therefore possible that it is composed by the translator, although it conspicuously does not discuss the activity of translation itself. In the second appendix, I have transliterated the preface in full, leaving it to the interested reader to read and translate for themselves.

Let me move on now to the two xylographic Mongolian titles. The first is a copy of Ilan hacin-i gisun kamcibuha tuwara de ja obuha bithe | Γurban ǰüil-ün üge qadamal üǰeküi-dür kilbar bolγaγsan bičig | 三合便覽, call number TA161/1471, in 12 volumes and housed in two cases. It is a well-known textbook of Mongolian and Manchu published by Sio Šeng Fugiyūn 秀升富俊 (1748–1834) based on the compilation of Ging Jai Gung 敬齋公, notable for its inclusion of a list of correspondences between Mongolian and Manchu grammatical particles as well as its phonetic transliteration of Mongolian words using the Manchu script. The preface is dated to 1780, and the title page of this copy specifies that it is a 1792 reedition.

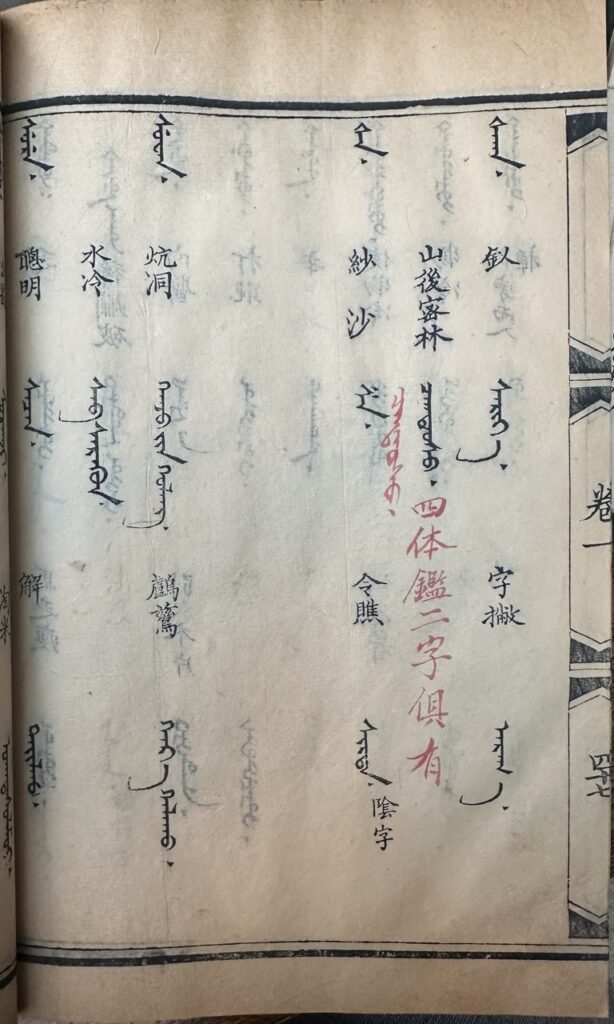

This copy is extensively annotated; it includes corrections to the Mongolian in red ink and additions of word sets (in Manchu, Chinese, Mongolian, and Kalmyk) in the top margin in black ink. It is especially notable for the systematic addition of Kalmyk or todo bičig glosses next to the Mongolian words in all but last two volumes, and on very rare occasions (for example, for the word imhe = 翼 = udirapalgüni, which is the name of a constellation in Chinese and Vedic astrology, 2:125r) the use of Tibetan gloss (in this case, dbo). (Image: 4:1r of TA161/1471 Ilan hacin-i gisun kamcibuha tuwara de ja obuha bithe | Γurban ǰüil-ün üge qadamal üǰeküi-dür kilbar bolγaγsan bičig | 三合便覽. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

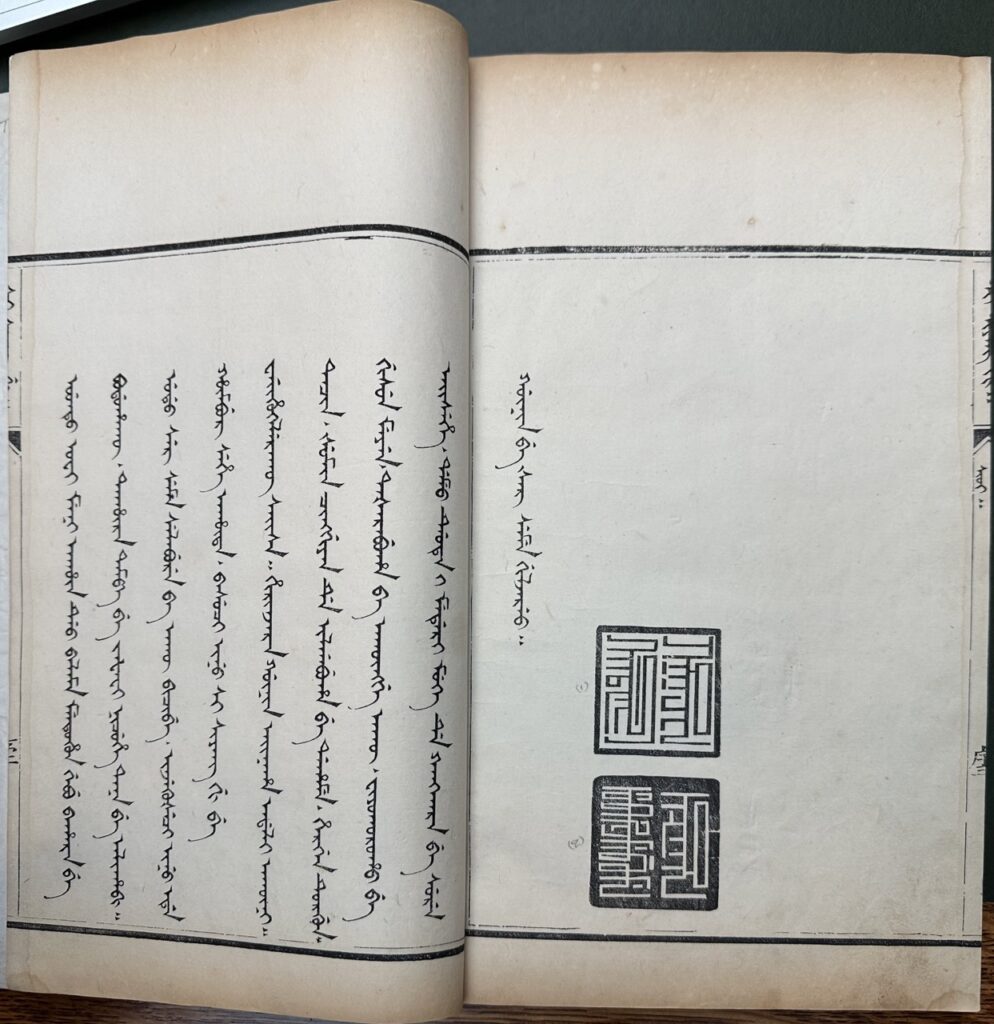

It is significant, then, that two red seals reading “富俊之章” and “紹衣堂” appear at the end of the preface in vol. 1, as they suggest that this had been a copy owned by the editor Fugiyūn himself. Martin Heijdra has made the reasonable suggestion on this basis that the annotations were made by Fugiyūn with the intention of publishing a new edition of the book, expanded, corrected, and with todo bičig included for each entry.

The dates of the todo bičig annotations can be further delimited by a close examination of the fourth volume, which had sustained significant damage over time and skillfully repaired, with new paper fused onto the old ones and the missing text supplied in fine, but cursive, handwriting. On the repaired part of the first leaf of this volume is a partially-legible date “戊申十二月??,” which can only be 1848 or 1908 given the work’s publication date, both of which postdating Fugiyūn’s death. On the second leaf of that volume part of the top margin bearing an added word set has been lost and replaced by new paper, and since the annotation is broken off where the original and new paper is fused, it is clear that the repairs had been done after the todo bičig annotations.

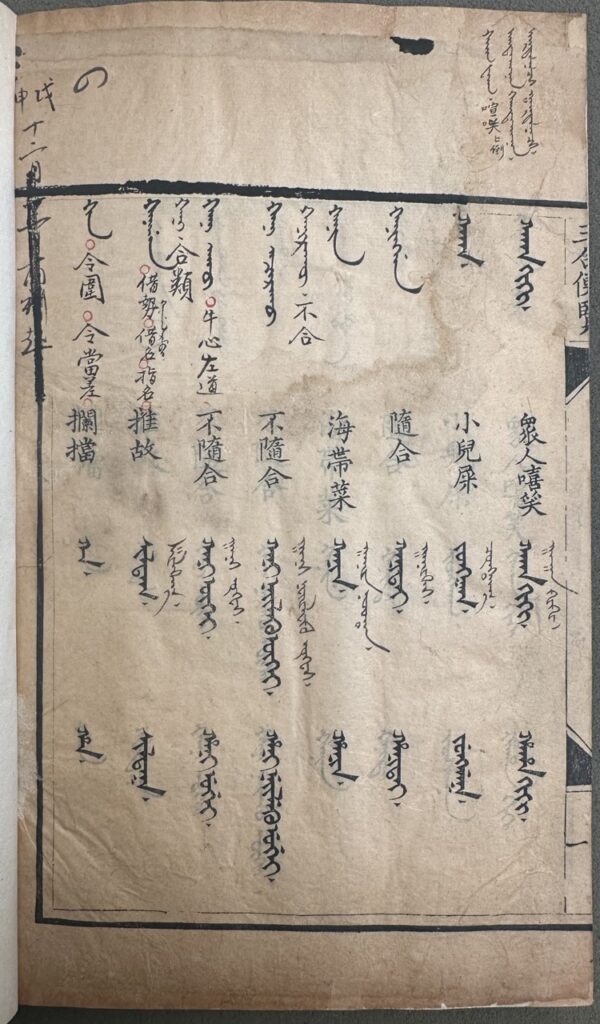

The second xylographic Mongolian title, coincidentally also bearing handwritten annotations by its author, is a collection titled 蒙文四種 (from the title-slip on the case), call number TA161/3237, published almost exactly 50 years after Fugiyūn’s textbook. It is a collection of four works, all of which Mongolian language learning materials by Ho Ting Saišangga 鶴汀塞尚阿 (1794?–1875), bound into four volumes and housed in one case. The first two works—Mongγol üsüg-ün ǰirum-i salγaγsan bičig | Monggo hergen-i jurgan be faksalaha bithe | 蒙文晰義 and Mongγol bičig-ün qaulitu dürim bičig | Monggo bithe-i koolingga durun bithe | 蒙文法程—are materials Saišangga’s father used to instruct him in the Mongolian language, while the third and the fourth work—Üǰeküi-dür kilbar bolγaγsan bičig-ün tasiyaraγsann yabudal-i ǰalaraγuluγsan bičig | Tuwara de ja obuha bithei tašaraha babe tuwancihiyaha bithe | 便覽正訛 and Üǰeküi-dür kilbar bolγaγsan bičig-ün tasuldaγsan-i inu nökülgilegsen bičig | Tuwara de ja obuha bithei melebuhengge be niyecetehe bithe | 便覽補遺—are his own supplements to Fugiyūn’s trilingual textbook. The prefaces of all these works date to the tenth month of Daoguang 28, or 1848. (Images: 1:3v and 1:47r of TA161/3237 蒙文四種. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

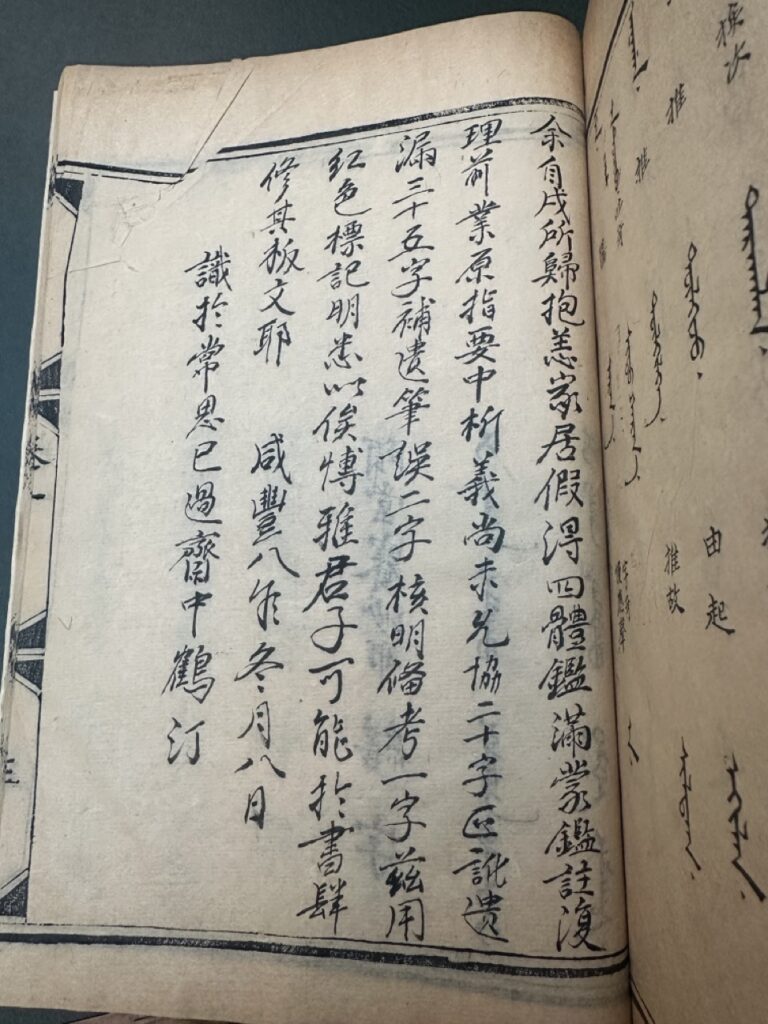

Like the previous item, this copy is uniquely valuable for containing handwritten annotations by the author himself. Saišangga writes in a handwritten note on the verso of the third leaf in volume 1:

余自戎所歸,抱恙家居,假得四體鑑滿蒙鑑註,復理前業,原指要中析義尚未允協二十字,正訛遺漏三十五字,補遺筆誤二字,核明偹考一字,茲用紅色標記明悉,以俟博雅君子可能扵書肆修其板文耶。咸豐八年冬月二日 識扵常思已過齋中鶴汀。

I have returned from war and resided home due to illnesses. Having borrowed the Quadriglot Mirror and the Manchu-Mongol Mirror commentaries, I returned to my previous publication. In the first work there are 20 entries with inaccuracies, in the third work there are 35 omissions, in the fourth work there are 2 errors, and in Beikao 1 entry is clarified. I have clearly marked all these in red ink, so that a learned gentleman might published a revised edition. Written by Ho Ting, in the eighth year of Xianfeng, the second day of the eleventh month, in the Study of Often Contemplating One’s Faults.

Do forgive the rough translation I give here (and earlier). The point is, near the end of 1858 (a decade after these works have been printed), Saišangga had returned to them and added corrections in red ink, based on a few borrowed editions of the Qianlong-era polyglot Mirrors. These annotations in red are clearly visible throughout Princeton’s copy of the work.

One last thing to note about this copy is that at one point, it likely belonged to a student named Wenhing or 文興, as the name (in Manchu and Chinese) appears on the covers of the volumes, but is sometimes blotted out or pasted over. It is unclear whether Wenhing used the books before or after Saišangga had annotated them.

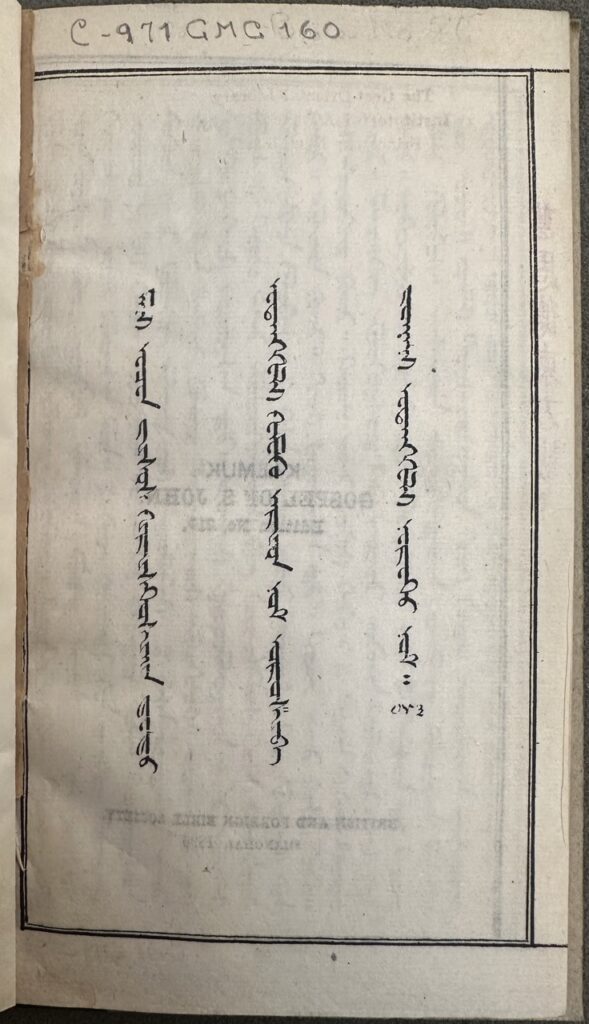

Let me conclude this two-part blog post by mentioning two early specimens of Mongolian movable type printing, which are not unique items but nevertheless relatively unusual. One of them is Mani ezen yisus kiristosiyin dedü evanggeli kemekü ariun nom orošiba yoġani evanggeli neretü nom | Gospel of John in one volume, call number TC971/120.cjiz.ll, printed in todo bičig by the British and Foreign Bible Society in Shanghai in 1896. The verse numbers are given in Tibetan numerals, and the volume appears to have been rebound—the first leaf (page number 455) begins only with John 1:17. (Image: Cover of TC971/120.cjiz.ll Mani ezen yisus kiristosiyin dedü evanggeli kemekü ariun nom orošiba yoġani evanggeli neretü nom | Gospel of John. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

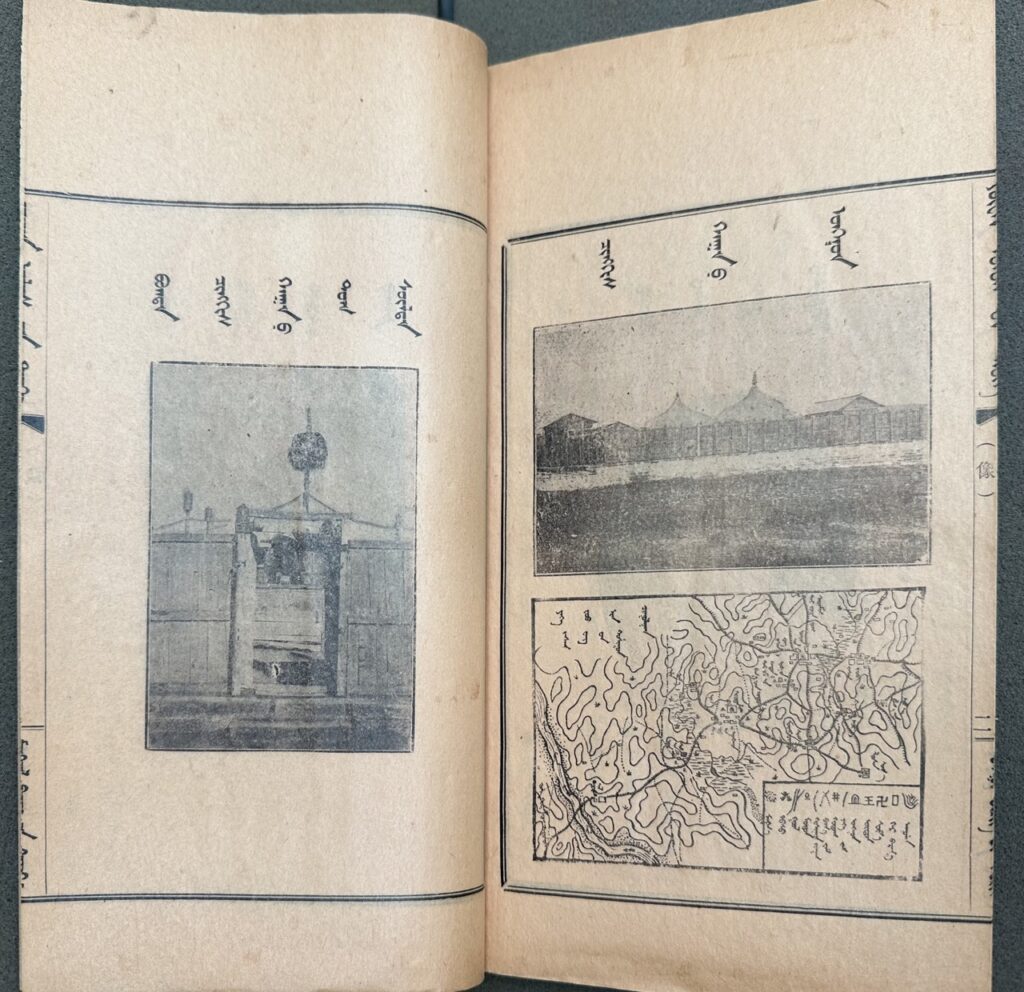

The other title—printed less than a century ago—is a set of four volumes titled Yüwen ulus-un teüke, call number TB12/2453. The label on the case reads, in Chinese, “元史演義,” but this is in fact an early, twelve-chapter edition of the famous Köke sudur finalized by Injannasi (1831–1896), whose full title (given inside the volume) is Yeke yüwen ulus-un manduγsan törü-yin köke sudur. On the back cover we find the publisher information given as “Mongγοl bičig-ün qoriyan_a darumallabai 北京蒙文書社出版,” from which we know this to be the movable type edition published by the Mongolian typographer Temgetu (1888–1939), also known in Chinese as Wang Ruichang 汪睿昌, of the Kharchin Right Banner. The preface—not signed, but unlikely to be written by anyone other than Temgetu—discusses the importance for Mongols to understand their own history, a sentiment that very much resonated with that of Köke sudur’s author, even if Inhannasi’s own prefaces are not included. The copy itself is undated, but we know it to have been published sometime in the 1920s, during which Temgetu also published a number of Mongolian textbooks and other historical works.

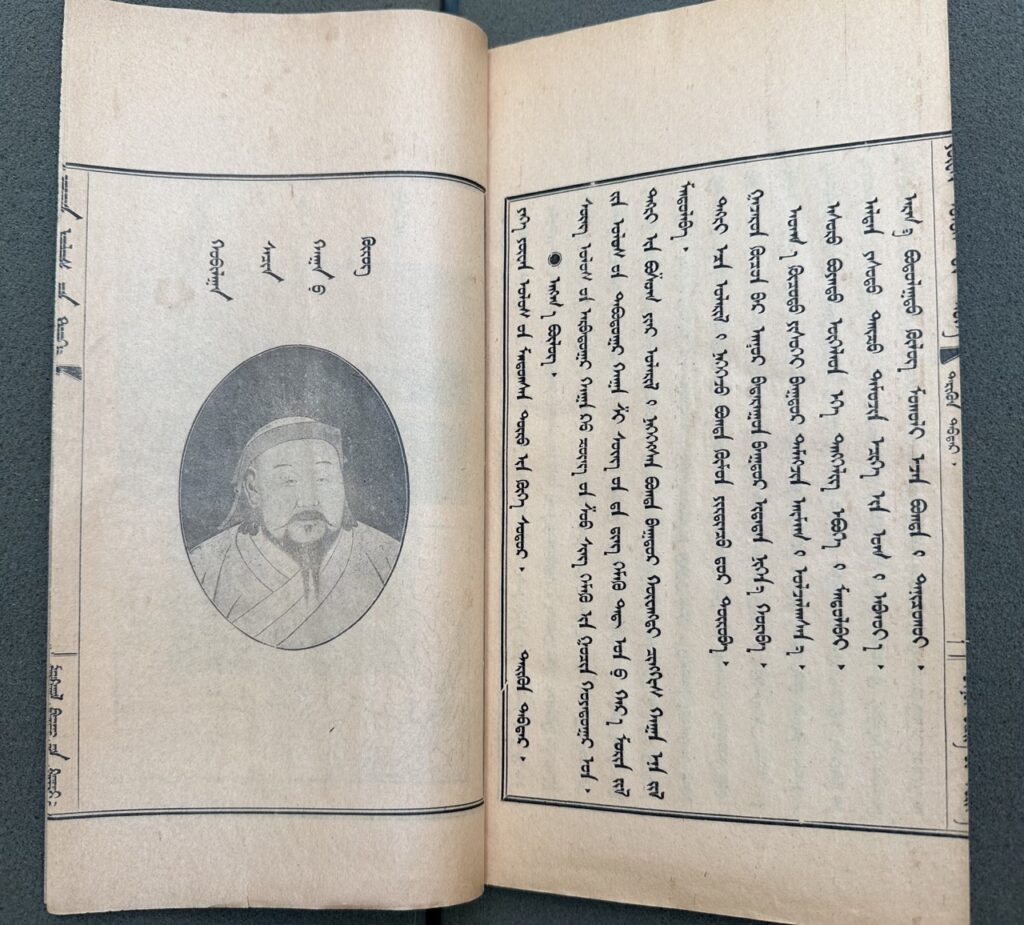

The book, despite being printed with movable type, is made to resemble a woodblock-printed book, with “frames” (which are imitated—pay attention to the break at the corners) and banxin 版心 inscriptions. These more traditional elements are fascinatingly juxtaposed against five illustrations at the beginning of the historical novel, two of them lithographically reproduced photographs and the other three, though not photographs, are nevertheless printed lithographically rather than xylographically. The five images, in sequence, are an image of Chinggis Khan, “baγda činggis qaγan-u doγ sülde,” “činggis qaγan-u ongγon,” a map, and an image of Kublai Khan. At least one of the images—that of Kublai Khan—was recycled from an earlier publication of Temgetu’s, the eight-volume Mongγol udγ_a-yin surγahu bičig of 1923, as Sarantuya’s 2017 article demonstrates. (Images: Illustrated pages at the beginning of vol. 1 of TB12/2453 Yüwen ulus-un teüke. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University Library.)

Appendix II: Manchu preface of TD143/1881 Ubaliyambuha si siyang gi bithe.

wargi asgan [=ashan] serengge . dergi baita waka kai sehengge .. asgan sere hergen de tob cin ci tucikekū be serebufi . wargi sere hergen de tuwancihiyame getukelehebi .. baita jaka-i banin yongkiyabume yongkiyabufi . gūnin mujilen-i turgun akūmbume akūmbuhabi .. muwa oci šošohon oyoki . narhūn ohode jorin šetuken [=getuken] .. šu-i yabubun sidehunjeme teodenjeme lohobuhakū . ilhi jergi-i hergen tome dubibuhekū .. koco wai-i songko be ambuhakū . siren sudala-i jun be mohobuhakū .. julge ci lakcame tucifi . amaga ci iletu colhorokobi .. beyei oori simen be yadabufi gūwa de doko arame . ini umgan šugi be olhobufi weri de ildun obuhabi .. da dube ishunde ašumbufi . duben deribun si bi karmatahabi .. ambula bime largin akū . labdu bime subsi akū . fun beye . behe de tucibufi .. weihun arbun . hoošan de ebubuhebi .. yala gūla . uthai gehun .. minggan aniya-i yabun songko . nergin de gukubuhekū .. tanggū jalan-i muru dursuki . ne je sabubuhabi .. ere mujilen usiha borhofi biya ohongge . elden isafi šun ohongge .. ere mujilen be bahara de mangga . teisulebure de ja akū ofi . ere mujilen baha be ulame . šumin goro jombume meni meni mujilen hairara be hir seme senggihabi .. ya emu ba nei taran waka . ai gisun seme senggi sabdan akūni .. nenehe ursei gūnin . tai šan alin-i adali . waššaha seme ekiyendere aibi . nonggibuha seme muture aibi . uttu ofi meni ahūn deo balama mentuhun gebu bahara be bodohakū . tahūra tampa be jafafi nicuhe tana be alihabi .. udu ser seme selabure ba akū bicibe . injekušeci inu ede hūmbur sehe ahūta . basuci inu si siyang gi be weihukelerakū saisa .. hirinjara gūnin ainaha adali akūni .. tacin . šumin cinggiyan de ilgabuha be dahame . hergen turgun . gisun meyen . tašarabuha ba akūngge akū . fiyokoroho be aisehe . damu deote-i mederi muke de kangkara be sure gūnin be šar seme giljareo ..